FHB Highlight: «Hispanidad»

ELENA DÍAZ-GÁLVEZ PÉREZ DEL PUERTO

Mª TERESA VIDAL VIDAL

October 2021

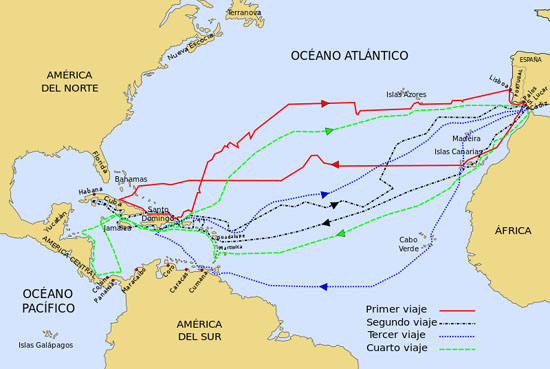

The expedition set sail from Palos de la Frontera on 3 August 1492 with three ships, the Santa María (with Columbus aboard), the Pinta (captained by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón) and the Niña (commanded by Martín Alonso Pinzón) and a crew of between 96 and 120 men, depending on the authors. Three days after setting sail, the Pinta’s rudder broke, forcing them to stop, for almost a month, in the Canary Islands. After several weeks in the Atlantic, and due to the crew’s frustration and discontent with the living conditions on board, a mutiny broke out on 6 October but it was subdued thanks to the intervention of Martín Alonso Pinzón. Finally, at two o’clock in the morning on 12 October, Juan Rodríguez Bermejo, known as Rodrigo de Triana, sighted a coral island in the Bahamas archipelago, which was given the name of San Salvador. It was on this island that the first documented encounter took place between Europeans and the indigenous people of the American continent, who from then on were known as Indians, as Columbus claimed he had arrived in India. After landfall, Columbus spent three months exploring the discovered territories and on 15 March 1493 he arrived back in Palos with the Santa Maria, where he was received triumphantly. After that first voyage, Queen Isabella authorised Columbus with three more voyages in which areas of what is now Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Venezuela, Panama and Costa Rica were discovered, explored and colonised.

(Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, www.cervantesvirtual.com)

The New World

Although it is an irrefutable fact that it was Columbus who established the definitive contact between the Old and the New World, it is less clear whether Columbus was aware that he was facing a new continent or whether he clung to the idea that he had reached the Far East as described by Marco Polo. Perhaps because of this and because it was the Florentine explorer and cosmographer, naturalised Castilian, Amerigo Vespucci who first realised, on 17 August 1501, that present-day Brazil was not part of Asia but a New World, this new continent was christened America by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, in a map published on 25 April 1507.

While Spain enjoyed the benefits of the discovery of America, Portugal continued with its expansionist ambitions and the ongoing disputes between the two kingdoms had to be resolved with the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This treaty, blessed by Pope Alexander VI, established a line that, with its ends at both geographical poles, passed 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands and divided the globe into two hemispheres, with the territories to the west of the line belonging to Spain and the territories to the east to Portugal.

While the Treaty of Tordesillas allowed Portugal to claim a large part of the territories of the New World, mainly Brazil, Portuguese navigators continued their voyages of exploration. In 1498, after the longest ocean voyage to date, Vasco da Gama reached India, opening up a new sea route between the West and the East.

Magellan and Elcano Expedition

In February 1518, the soldier and navigator of noble descent Ferdinand Magellan and the cosmographer Ruy Falero, both Portuguese, but feeling that they had been unfairly treated and not given enough consideration in their own country, presented the Spanish King Charles I with a project to reach the Spice Islands by sailing westwards along a route “shorter and different from the one discovered by the Portuguese”, seeking a passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the South Sea, discovered by Núñez de Balboa in 1513. The project was vehemently opposed by the King of Portugal, who tried to frustrate the success of the venture with different strategies, ranging from trying to convince Magellan to give up the plan to planning an attempt on his life or chasing the Spanish ships to prevent their return.

To the same objective of finding a new route to the Spice Islands that Columbus had had years before, Magellan incorporated the idea that these islands would be in the hemisphere which, according to the Treaty of Tordesillas, was under Spanish sovereignty and not in Portuguese territory. The Spanish crown financed around eighty percent of the cost of the expedition, using part of the gold that arrived from the Indies; the rest was provided by the banker from Burgos, Cristóbal de Haro.

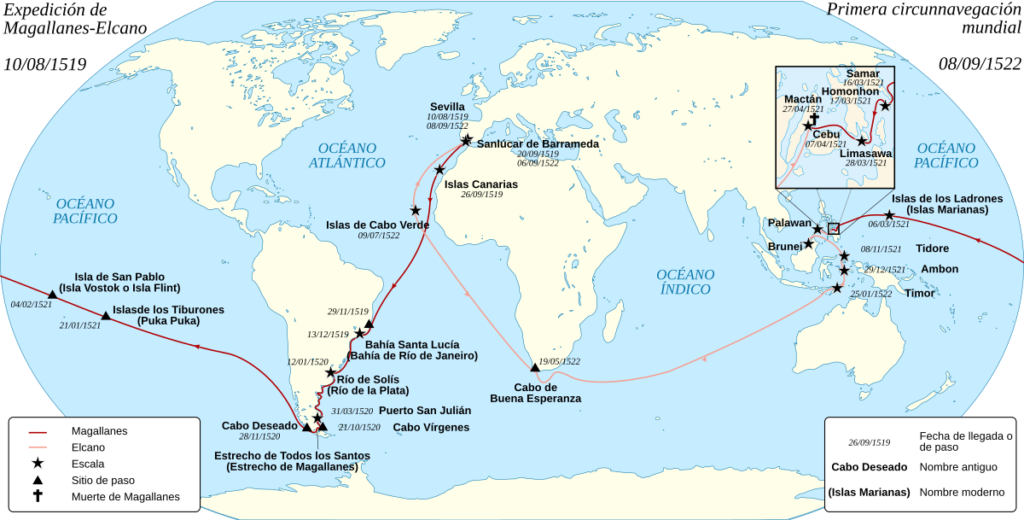

The expedition comprising five ships (Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepción, Victoria and Santiago) and around 250 men, captained by Magellan in command of the Trinidad, set sail from Sanlúcar de Barrameda on 20 September 1519 after sailing down the Guadalquivir from Seville. After calling at the Canary Islands, they continued along the coast of Africa to Sierra Leone and from there crossed the Atlantic to what is now Rio de Janeiro continuing along the coast to the south. When they reached what is now the estuary of Rio de la Plata, the widest in the world, they thought they had found the passage to the South Sea, only to be disappointed to find that it was an inlet 300 kilometres into the continent. From there, they continued along the coast until they found shelter for the winter in a bay in Argentine Patagonia, which they called “Puerto de San Julián”.

From the beginning of the voyage, Magellan exhibited an excessively authoritarian attitude and allowed himself certain breaches of royal instructions, which caused discontent and mistrust among the crew which, together with the deterioration of living conditions on board, precipitated a mutiny led by Juan de Cartagena, captain of the San Antonio and inspector general of the fleet. The mutineers wanted to return to Spain, believing that the passage had not been found and that the expedition had therefore failed. After managing to crush the mutiny, they continued sailing south and Magellan’s tenacity was finally rewarded when they found the passage and reached the South Sea, even at the cost of losing the Santiago as a result of a storm and the desertion of the San Antonio, which returned to Spain, due to the hunger, cold and bad weather suffered by the crew.

De Magellan_Elcano_Circumnavigation-fr.svg: Sémhurderivative work: Armando-Martin (talk) – Magellan_Elcano_Circumnavigation-fr.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15231454

Once in the Pacific, named as such by Magellan for the calmness of its waters, and after a long voyage marked by hunger and scurvy, they first landed on the island of Guam (in the Mariana Islands) and later in the Philippines, where Magellan died in a battle with the natives on the island of Mactan, near Cebu. The expedition got rid of the Concepción, which was badly damaged, and the crew was divided between the Trinidad, which attempted to return to Spain via the Pacific and failed, and the Victoria, under the command of Juan Sebastián Elcano, which continued along the Portuguese route, sailing west.

Elcano decided to sail without any stopovers to avoid being intercepted by the Portuguese, which would have meant the end of the expedition. They only allowed themselves just one stopover in the Portuguese colony of Cape Verde, in order to buy food because of the crew’s hunger and exhaustion. Pretending to be a ship returning from America, they managed to stock up, but they were discovered and had to flee, being chased by four Portuguese ships. Finally, three years after the departure, on 6 September 1522, the Victoria returned to Sanlúcar de Barrameda with eighteen men on board, having completed the first round-the-world voyage of which we are celebrating the V centenary. The ship came back with, among other goods, a cargo of clove that could pay for the whole cost of the expedition. The feat and its effects would grant Spain that “empire on which the sun never set”.

Juan Sebastián Elcano, Spanish Navy training ship

Following in the wake of the Victory, the Spanish Navy training ship Juan Sebastián Elcano has circumnavigated the globe eleven times, the last one this year as part of the V Centenary celebrations. Coinciding with this anniversary, the British Hisapnic Foundation has scheduled a trip to Cádiz that includes a visit to the training ship to commemorate the achievement of that first round-the-world voyage. In addition to its primary mission of training Marine Guardsmen in their fourth year, the training ship Juan Sebastián Elcano also performs functions in support of the State’s foreign policy, carrying the national flag in all the countries it visits, and receiving different national and foreign authorities on board, earning the recognition and affection of those who visit it.

Bibliography, readings and complementary resources:

- Blanco Nuñez, J. M. (2019). Las navegaciones oceánicas de la primera vuelta al mundo (1519-1522). Cuadernos de investigación histórica, 36, 187-220. https://doi.org/10.51743/cih.86

- Chaín-Navarro, C. (2018). Egipcios y romanos en la India. Blog Cátedra de Historia y Patrimonio Naval. (https://blogcatedranaval.com/2018/02/07/egipcios-y-romanos-en-la-india/)

- Crespo MacLennan, J. (2018). Europa. How Europe Shaped the Modern World. First Pegasus Books. New York. (ISBN: 978-1-68177-756-6).

- Hereter, Román (2019) El Comercio De Las Especias Orientales Desde La Antigüedad a Las Cruzadas: Un Estudio Geopolítico. Tesis Doctoral. Universitat Autònoma De Barcelona. Departament De Ciències De L’Antiguitat I De L’Edat Mitjana. Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10803/665834.

- Mascareñas Pérez-Iñigo, J.M., Mascareñas Gónzalez, A. (2012). El comercio de las especias como factor principal que impulsó los descubrimientos geográficos de Europa Occidental. RUE: Revista Universitaria Europea, 16, 73-95. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4077036

- Montojo Sánchez, L. (2019). Los orígenes de un mundo global. Marco histórico del viaje de Magallanes y Elcano en el contexto de la celebración del V centenario de la primera circunnavegación. Cuadernos de investigación histórica, 36, 73-92. https://doi.org/10.51743/cih.81

- Rodríguez González, A. R. (2019). La primera vuelta al mundo (1519-1522). Cuadernos de investigación histórica, 36, 115-138. https://doi.org/10.51743/cih.84

Web resources:

- www.vcentenario.es/

- www.primeravueltaelcano.es/

- www.facsimilefinder.com/facsimiles/imago-mundi-facsimile

- sge.org/publicaciones/numero-de-boletin/boletin-48/la-expedicion-de-cristobal-colon/

- www.cervantesvirtual.com/portales/cristobal_colon/cristobal_colon/

- www.elmundo.es/espana/2021/09/18/6144cdcae4d4d8a2398b459a.html

- Yanes, J. (2021) en https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/ciencia/grandes-personajes/americo-vespucio-cosmografo-nombre-america-error/

Historical novel:

José Calvo Poyato (2019). La ruta infinita. Harper Colins Ibérica S.A., Madrid (ISBN:978-84-9139-397-9).