FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE´S WORK

Harley Hospital

Her first job was in 1852 at the Women’s Hospital on Harley Street, a London hospital where her innovative and efficient way of working, along with her scientific knowledge and training, made such an impression that very soon, in August of 1853, at the age of 33, she became a nurse supervisor. With the passage of time and the new methods of Nightingale, the small sanitarium became one of the best hospitals in England. Around those years, Florence also volunteered at a Middlesex hospital struggling with a cholera outbreak and unhealthy conditions that led to the rapid spread of the disease. (This fact is reflected in the British television series “Victoria”, where Florence Nightingale is played by actress Laura Morgan)

Laura Morgan plays Florence Nightingale in the series VIctoria

Season 3 ⎟ Episode 4

Crimean War

In October 1853, the Crimean War (1853-1856) broke out, a warlike confrontation between the Russian Empire and the coalition formed by France, Great Britain, the Ottoman Empire and the kingdom of Piedmont – Sardinia. Thousands of British soldiers were sent to the Black Sea, where supplies rapidly decreased. After the Battle of Almá, England was shocked by the abandonment of its sick and wounded soldiers, who not only lacked sufficient medical care due to hospitals being understaffed, but also languishing in appallingly unsanitary conditions.

Hearing the horrible stories and news about the wounded and the conditions in which they were being treated, Florence sent a letter to Sidney Herbert, Secretary of State for War, offering her services as a volunteer. Thanks to her friendship with him, she received an affirmative answer. Florence Nightingale left from London with a group of 38 nurses of various religious orders and sailed with them to Crimea. It was the first time that women were allowed to officially serve in the military.

On November 4, 1854, Florence and the 38 volunteers, Catholic and Protestant, arrived in Scutari (Üsküdar), today a neighborhood of Istanbul. Although they had been warned of the horrible conditions there, nothing could have prepared Nightingale and his nurses for what they saw when they arrived. What they found at the base hospital in Constantinople where British fighters were admitted was absolutely Dantesque. The hospital settled atop a large cesspool that contaminated the water and the building itself. The patients lay on stretchers strewn about the corridors on a grimy floor, the rain poured down the ceiling, there was hardly any running water, the facilities were riddled with parasites, the dirt was overflowing everywhere and the food was pitiful.

The most basic supplies, such as bandages and soap, became increasingly scarce as the number of sick and wounded increased. Even the water needed to be rationed. More soldiers died from infectious diseases, such as typhoid and cholera, than from injuries sustained in battle. Florence greatly improved the sanitary conditions of the hospital. Her “caretaker angel” figure was praised, but her true role was organizing.

She purchased hundreds of scrub brushes and asked less ill patients to scrub the interior of the hospital from floor to ceiling. Florence and her team worked hard on cleaning and also on the diet that the patients had to follow. Nightingale instituted a “disabled kitchen” where appetizing food was prepared for patients with special dietary needs. It also established a laundry room for patients to have clean bedding, as well as a classroom and library for intellectual stimulation and entertainment. In addition, with the authority that being a director gave her, she got military engineers to fix the water leaks and improve their purification.

Jerry Barrett National Portrait Gallery, Londres.

Even the best efforts could not reduce the total number of deaths, which increased steadily and reached 4,000 in a single winter. Although Florence had made the hospital more efficient, it was no less deadly. Horrified by the loss of life, her comments and ideas were heard by Queen Victoria I, who supported Nightingale’s plans regarding the reform of the military medical service. With the Queen’s backing, she persuaded the government to establish a commission to investigate the health of the army. In the spring of 1855, the British government sent a health commission to investigate conditions at Scutari. She discovered that the military hospital was built over a sewer, so the patients were drinking contaminated water. The solution was to clean the polluting landfills and improve ventilation in that hospital and others. And the result: fewer deaths.

Renowned statistician William Farr and John Sutherland of the health commission helped her analyze vast amounts of complex data, and the truth they revealed was shocking: the cause of 16,000 of the 18,000 deaths were not injuries sustained in battles but preventable diseases, whose contagion was due to poor hygiene. Florence created the rose diagram to present her health statistics, an easy way to explain deaths, this representation indicated a 99% decrease in deaths after the work of the health commission.

In 1856 the war ended giving victory to the coalition in which Great Britain was a member. Nightingale had remained in Scutari for a year and a half, left after the conflict was resolved, and returned to her childhood home in Lea Hurst. After the details of her hard work reached the press, she became a much-loved and popular figure across the UK, and to her surprise she was greeted with a hero’s welcome, a reception the humble nurse would have wanted to avoid. She liked popularity so little that on her return she traveled under the pseudonym Miss Smith.

The legend of “The Lady with the lamp”

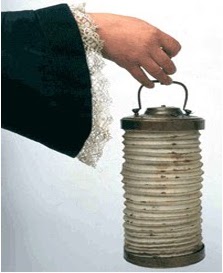

Florence spent every waking minute caring for the soldiers. In the afternoons she moved through the dark corridors carrying a lamp as she made her rounds, attending patient after patient. The press, like The Times, related the painful conditions of the soldiers and in one article created the legend “The Lady with the Lamp”, who tirelessly cared for the wounded at the British hospital in Scutari at night.The sick soldiers, moved and consoled by the care and compassion of Florence, in addition to calling her “The Lady of the Lamp” also baptized her with the nickname “The Angel of Crimea” and began to call the nurses “Nightingales”, since NIGHTINGALE, Florence’s last name, is the name of the bird.

A multitude of poems, songs and plays were written in her honor. Such was her popularity that her family received a sea of poems that admirers sent to Florence and the image of the “Lady of the Lamp” was printed on bags and souvenirs. Florence never liked being famous but she took advantage of her popularity for the benefit of society and the army to continue saving lives and promoting the cause for which she was determined.

“”This Turkish lantern, or fanoos, was used in Scutari during the [Crimean] war. It is the same traditional design as those used by Florence in her nightly rounds of the halls. The image of her holding such a lamp gave rise to the legend from ‘The Lady with the Lamp’: A Guardian Angel of the Troops. Artists often mistakenly depicted her holding a Greek lamp or genie lamp, which only added to the sentimental image “

????London Florence Nightingale Museum

Her contribution to an incipient Public Health

Following the hygienist currents of an incipient concept of public health that would later take root in Britain, Florence changed military hospitals: she ended the beds shared by soldiers dressed in their dirty clothes, got bedding, enabled a laundry, drove the landfill away and managed to ventilate the rooms and improve the diet of the sick. Through frantic activity, she successfully accomplished the reform of British military health services, the progressive extension of his model to civil health services, what we now call public health.

She was an authority on public sanitation issues in India for both military and civilians, although she had never been to India and throughout the US Civil War, she was frequently consulted on how to better manage field hospitals.

In 1858 Florence published the book “Notes on Health, Efficacy and Hospital Administration in the British Army”, delving into what was observed in the Crimean War. In 1859 she published his most famous books, “Notes on Nursing” and “Notes on Hospitals”. By the 1880s, scientific knowledge had advanced in ways that further supported Florence’s reformist ideas. Like many medical practitioners, by then she also accepted the germ theory or microbial theory of disease.

In 1860 she founded the Nightingale Training School for Nurses

In 1855, Queen VIctoria had rewarded Nightingale’s work by presenting her with an engraved brooch that became known as the “Nightingale Jewel” and by awarding her a£250,000 prize from the British government.

Her work in the following decades helped establish nursing as a respectable career for women and improved hospitals so that they became clean and spacious places for patients to recover. In 1860, Nightingale decided to use the money to promoting her cause, she founded a nursing school in her name, the “Nightingale Nurse Training School”, at St. Thomas Hospital, a school where many of the best nurses of the 19th century were trained. Today, it still exists as an academic school within King’s College London.

Florence became a highly admired figure and young women aspired to be like her. Eager to follow their example, even wealthy upper-class women began to enroll in vocational school, nursing was no longer frowned upon by them, in fact, it had come to be regarded as an honorable vocation.

The end of her stage as a nurse

During the 1860s, Florence Nightingale stopped practicing as a nurse, as the effort made in Crimea affected her deeply. While at Scutari, Nightingale had contracted the bacterial brucellosis infection, also known as Crimean fever, and would never fully recover. Shortly after her return from Crimea, at 38, she began to suffer from health problems, was confined to her home and was usually bedridden from where she continued her work.

She fought to improve health services by examining statistical data from her sickbed, doing pioneering work that spread throughout the world. Working to improve the service, she created a Hospital Statistics Model through which information on patients was collected and statistics on operation were generated. Residing in Mayfair, she continued to be an authority and advocate for health care reform, interviewing politicians and welcoming distinguished visitors from her bed.

The end of her life

In August 1910, Nightingale fell ill, died at her London home at the age of 90, on Saturday, August 13, and had expressed the wish that her funeral be a quiet and modest matter. Despite the desire of so many to honor Florence Nightingale, respecting her last wishes, her relatives rejected a national funeral as well as the offer for a national funeral at Westminster Abbey, where Florence would have rested alongside personalities such as Newton, Dickens, David Livingstone , Rudyard Kipling …. The “Lady of the Lamp”, according to her last wishes, was buried in her family’s plot at St. Margaret’s Church, East Wellow, in Hampshire, England.

The ROYAL RED CROSS award was established on 23 April 1883 by Queen Victoria, with a single class of Member and first awarded to the founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale. Three years before her death in 1907, as a reward for her extraordinary services, King Edward VII had awarded Florence Nightingale the ORDER OF MERIT, being the first woman to receive this recognition given for extraordinary services in the field of the army, science, art or literature. In 1908 she was awarded The Keys to the City of London.

In 1883 Forence was the first person awarded

by the Queen VIctoria with the Royal Red Cross

In 1907 Florence was the first woman who received

the Order of Merit awarded by the King Edward VII