FHB Highlight: «Hispanidad»

ELENA DÍAZ-GÁLVEZ PÉREZ DEL PUERTO

Mª TERESA VIDAL VIDAL

October 2021

Throughout history, the territory that Spain now occupies has been populated and disputed by different civilizations; the Phoenicians and Greeks were the first to colonize our coasts, the Carthaginians and Romans fought for their control, the Arabs managed to conquer almost the entire territory and successive Christian kings established what, with the discovery of America, would become the WORLD´S LARGEST EMPIRE.

The cause of the beginning of the Spanish empire, and that of other European empires, can be found in the search for new routes to facilitate the spice trade, for which Europeans felt a hardly justifiable attraction and in the desire of Isabel the Catholic to evangelize new lands. Few dates have had such a profound effect on human history as that 12 October 1492 when three caravels captained by Christopher Columbus, in his search for a route to Asia from the west, landed on Guanahani, the island that was christened San Salvador and turned out to be part of a new continent. This discovery ushered in an era of expansion of European civilization in which the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula took an active part.

The official motto of Spain PLUS ULTRA (from the Latin, Beyond) was used for the first time in 1516 by Carlos I of Spain and since then it has been maintained until today.

Exploring the Atlantic in search of new trade routes

Until the beginning of the Age of Revolutions, at the end of the 18th century, and even in ancient times, European societies were captivated by the spices that came from Asia. It was this great demand that led the Romans, and later Portugal and Castile followed by Netherlands and England, to embark on a succession of daring expeditions in search of new routes to gain control of the trade. Although the reason for the Europeans’ fascination with spices is not clear, their use as food preserving agents, medicinal use or as a means of payment is suggested. Anyway, it was this extraordinary interest that was the incentive to finance the voyages that allowed Western Europe to discover new territories and to begin the European empires.

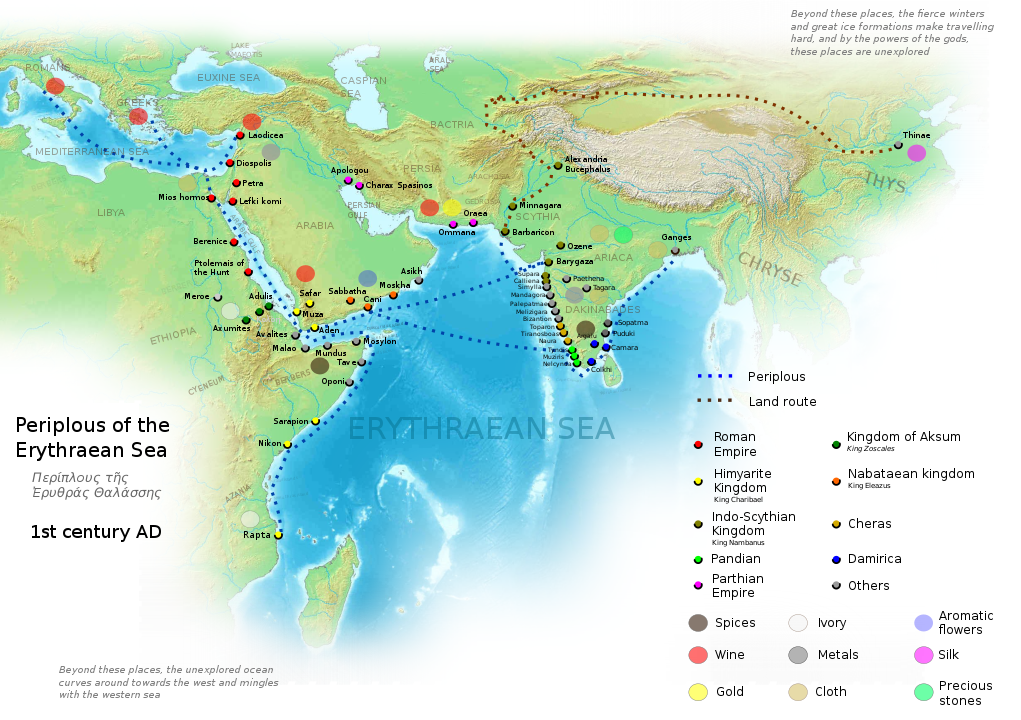

Although there is evidence that spices were highly valued as early as the end of the third millennium BC, and used by the Egyptians, Phoenicians and Greeks who traded them in the Mediterranean, it was the Romans who first established permanent trade routes with Asia. Rome was aware of the existence of China and knew that the most valuable spices came from territories east of India, but its maritime expeditions did not reach beyond the Ganges River. In India, Roman ships traded gold, silver, tin, valuable Mediterranean coral and the empire’s manufactures such as wine, glass and decorative objects for spices, especially large quantities of pepper, ivory, precious stones, muslin and tortoiseshell. Details of the voyage from Egyptian-Roman ports to India, with descriptions of the various ports and trading opportunities, are found in a Greek text known as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea dated to the mid-1st century AD by an unknown author.

From the beginning of the 4th century, with the division of the Roman Empire, the spice trade came under the control of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) thanks to the privileged position of its capital, Constantinople. However, Islamic expansion in both Central Asia and the southern Mediterranean made it impossible to maintain the routes from Christian territories and caused an exaggerated increase in the price of products transported along these routes, especially pepper. The interest in regaining control of these routes represents the economic background that, under the pretext of reclaiming the holy places, gave rise to the Crusades.

The rise of Italian cities such as Pavia and Venice, together with the Mongol invasions that weakened Muslim military power, allowed the revival of trade routes from Europe and merchants, such as Marco Polo (in the second half of the 13th century), to once again use the ancient silk route, facilitating the contact between East and West that had already existed in antiquity.

The fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 had again as a consequence for Europe the loss of trade routes with Asia, which came to be controlled by the Ottoman Empire. The need to find new routes led the small kingdom of Portugal, with a long maritime and naval tradition and an extensive coastline on the Atlantic Ocean, to take the initiative in expeditions to Africa. Previously, Ligurian sailors (as early as the 13th century) and from the Crown of Aragon at the beginning of the 14th century had begun to cross the Strait of Gibraltar and explore the Atlantic away from the usual coastal routes.

The first of the Portuguese expeditions during the reign of John I led to the conquest of Ceuta in 1415 and the establishment of a colony that allowed Portugal to strengthen its commercial position vis-à-vis other powers of the time such as Genoa and Venice. It was John I’s son, Prince Henry, known as Henry the Navigator, who, mainly for commercial interests, promoted voyages in search of a new spice route around Africa. Portuguese sailors gradually discovered the Atlantic coast of Africa; Gil Eanes sailed past Cape Bojador in 1434 and Bartolomé Díaz skirts the southern tip of Africa sailing through the Cape of Storms (later renamed Good Hope) reached the Indian Ocean in 1488.

While Portugal had consolidated its leadership in the Age of Discovery, the neighboring kingdom of Castile managed to challenge the Portuguese for this position thanks to the important contribution of Christopher Columbus.

It is believed that Columbus arrived in Portugal in 1476 as a survivor of a shipwreck in a naval battle between merchant ships and corsairs, and there he married and acted as a commercial agent, making frequent voyages during which he acquired maritime knowledge. His life in a society dedicated to the exploration of the Atlantic and in particular to the search for new routes to reach the land of spices allowed him to conceive and mature what Columbus himself called “the Indian enterprise”; to reach the Far East by a radically different route to the one usually used, bypassing Africa, sailing westwards across the Atlantic.

Columbus himself called it “the Indian enterprise”; to reach the Far East by a radically different route to the one usually used, bypassing Africa, sailing westwards across the Atlantic.

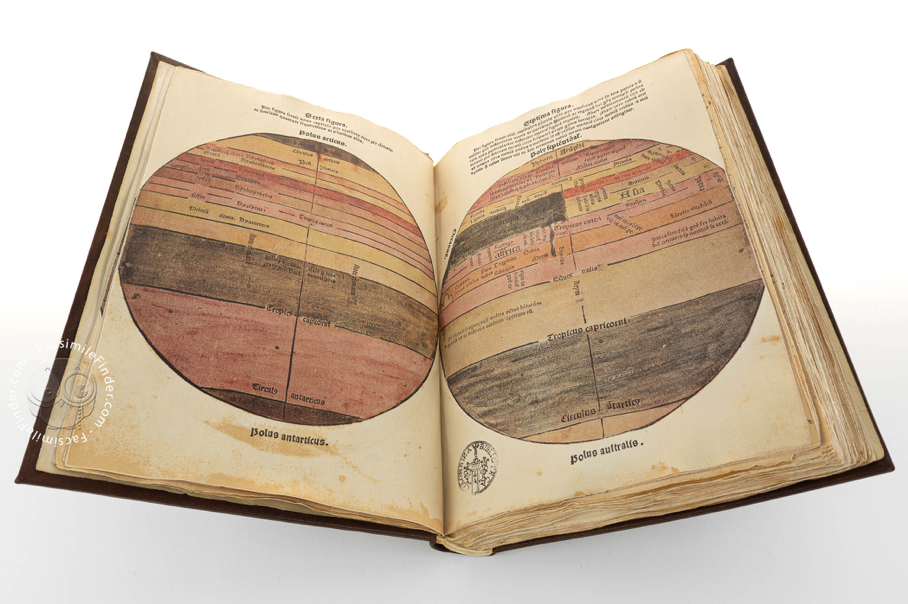

Columbus was particularly interested in the geographical theories of the time. His idea of reaching India and the mysterious Spice Islands (today’s Moluccas, the only region where nutmeg and cloves were produced) by sailing westward was based on knowledge of the sphericity of the earth, the theory of a single ocean that could be crossed by sailing westward, and the dimensions attributed to the globe, some of which were later proved wrong.

In order to carry out a project of such magnitude, it was necessary to have the support of a king or a powerful nobleman who would back and finance the project. Columbus therefore turned to the King of Portugal, John II, who, after discussing it with a board of experts, rejected the plan, both because the economic and political compensation demanded by Columbus seemed excessive, and because he considered some of the scientific assumptions of the project to be incorrect. After failing with Portugal, Columbus considered offering it to other European crowns, but he finally concentrated his efforts on its neighbor Castile, not only for reasons of proximity but also because the young Queen Isabella, married to King Ferdinand of Aragon, had ambitions to expand the dominions of her kingdom.

His idea of reaching India and the mysterious Spice Islands (today’s Moluccas, by sailing westward was based on knowledge of the sphericity of the earth, the theory of a single ocean that could be crossed by sailing westward, and the dimensions attributed to the globe.

Columbus arrived in Castile in 1485 where the first impressions of his project were not favourable and it was rejected on more than one occasion. The causes of the first refusals to Columbus’s aspirations are not clear, although different authors point to the opposition of Isabella the Catholic to renege on the terms of the Treaty of Alcaçovas, which divided the Atlantic dominions between Castile and Portugal, and to the fact that the Catholic Monarchs did not want to invest resources in any project other than the conquest of the kingdom of Granada. After several difficult years in which Columbus presented his initiative to the kings of Portugal, France and England, the Catholic Monarchs finally accepted the project and on 17 April 1492 the Capitulaciones of Santa Fe were signed. The agreement set out the terms of the project which established major concessions to Columbus. The final favourable decision, which did not come until the capture of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs, seems to have been due to a mixture of economic arguments because of the immense profits that could be made and political reasons, including the intention to corner Islam and the possibility, especially contemplated by the queen, of converting an unimaginable number of souls to the true religion.