FHB Highlight: «Hispanidad»

ELENA DÍAZ-GÁLVEZ PÉREZ DEL PUERTO

Mª TERESA VIDAL VIDAL

October 2021

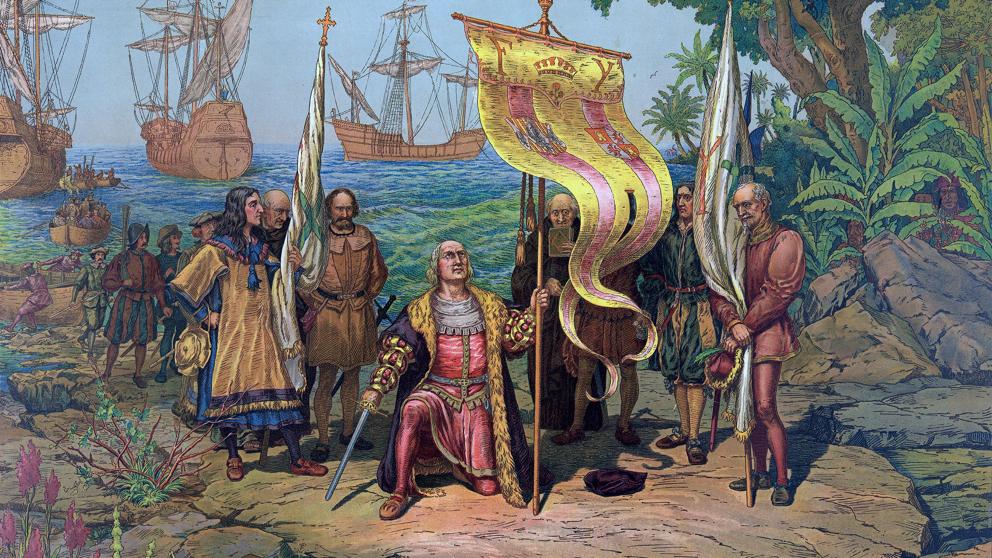

On October 12th, 1492, the expedition captained by Christopher Columbus reached the island of Guarani, in the Bahamas islands. Unbeknownst to them, they had just discovered a new continent and established the first contact between Europeans and Americans, wrongly called Indians because it was thought that they had gone around the globe and landed in India.

More than 400 years later, October 12 would become a day of celebration in Spain and many Latin American countries. The choice of this day had the added bonus that October the 12th commemorates the Day of the Virgen del Pilar, patron Saint of Hispanidad.

It was September 1892 and in San Sebastian the summer season was coming to an end, however, the Queen Regent Maria Cristina of Austria (widow of Alfonso XII) wanted to keep the court in the city for a few more days. Thus, on the 23rd she signed, on behalf of her son King Alfonso XIII, a Royal Decree declaring October 12th, 1892 a national holiday to commemorate the 4th Centenary of the Discovery of America. It should be noted that in the exposition of motives of this specific norm that the holiday is requested “without prejudice that the Crown with the Court can declare it perpetual afterwards”.

It was later called “Fiesta de la Raza”, since 1918, and “Día de la Hispanidad” since 1958. Enduring and adapted to political change, regional discrepancies and international situations during the 20th century, the celebration refers to the imperial past for the identification of the Spaniards, among themselves and with the world.

«The commemoration of the National Holiday, a common practice in today’s world, is intended to solemnly remember moments in collective history that are part of the common historical, cultural and social heritage, assumed as such by the vast majority of citizens.

Without prejudice to the indisputable complexity that the past of a nation as diverse as Spain implies, it must be ensured that the historical event that is celebrated represents one of the most relevant moments for political coexistence, the cultural heritage and the very affirmation of the state identity and the national uniqueness of that people.

(…) The date chosen, October 12, symbolizes the historical anniversary in which Spain, about to conclude a process of State construction based on our cultural and political plurality, and the integration of the Kingdoms of Spain into a Monarchy itself, begins a period of linguistic and cultural projection beyond European limits»

Law 18/1987, of October 7, which establishes the day of the National Holiday of Spain on October 12

Appearance of the term “Hispanidad”

The ideas of America, generated during the 19th century, will prepare those of the 20th century. For this reason, although the conjunctures leading to speak about “Hispanidad” are nineteenth century, the term as it is currently understood appears almost a century later, despite its historical traces. Specifically, the term “Hispanidad”, which at the beginning of the 20th century was hardly used and was anchored in the past, was revived by the priest Zacarías de Vizcarra in 1926 to replace the denomination until then predominant, that of Día de la Raza.

- “Hispanidad, generic character of all peoples of Hispanic language and culture;

- The whole and community of the Hispanic peoples”.

However, and despite the defence of such influential intellectuals as Ramiro de Maeztu of the term “Hispanidad”, the decree signed in 1918 by Antonio Maura and Alfonso XIII referring to the national holiday as Fiesta de la Raza would remain in force for many years.

First promoters of the idea of “Hispanidad”.

Rubén Darío, Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, Juan Valera, Rafael Altamira and Miguel de Unamuno were the ones who gave the idea of Hispanidad a concrete expression in thought through their writings.

The “hispanic being” of the 16th century created the historical realities of the New World and its heterogeneous identity from 1492 to 1824 based on:

1) The spirituality of Spanish humanism and Christian evangelization,

2) The juridical and humanistic code of the Laws of the Indies,

3) The direction of the monarchical State over the American political experience.

On these foundations, three centuries of coexistence and mutual cultural cession originated the Hispanidad.

During the reign of Isabel II (1833-1868) there was an economic crisis that turned America into a commercial market. The Spanish bourgeoisie and businessmen reinstated an image of the empire that had been cradled in the 18th century: America as a commercial market and as a factor in the defence policy of the two positions. However, this objective did not prosper due to the intervention of Spain in the internal affairs of Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina and Mexico, between 1842 and 1847.

In the mid-19th century, there was a change in Spain’s attitude towards Latin America.

During the Restoration (1875-1902) the pillars reflected in the nationalist idea of Hispanidad at the beginning of the 20th century were based on patriotism, the memory of the colonial Empire as the foundation of national greatness, the interests of the Castilian language, Christianity and the racist doctrine.

Spain’s maladjustment to modernity and the loss of its last overseas colonies collapsed this patriotism, however, and gave rise to a feeling of social degeneration. It was at this juncture that the Hispano-Americanist movement was born, a dynamic component for the resounding idea of Hispanidad.

Between 1880 and 1900, the Spanish Portuguese American Pedagogical Congress and the IV Centenary of the Discovery of America, among others, were commemorated. Likewise, several magazines and newspapers were created and disseminated, among them: La España Moderna (1889-1914) and the Revista de Historia y Literaturas Españolas, Portuguesas e Hispanoamericanas (1895). The Overseas Museum and Library was founded (1888). The confederative ideas of Simon Bolivar and the Restoration were re-discussed.

In summary, the Spanish-American rapprochement was made possible by:

1) the threatening imperialism of the United States,

2) the cultural concomitance among the Spanish-speaking nations, and

3) the attempt at a confederation.

Did the crisis of ’98 have a negative impact on Spanish-American relations?

Certainly not: Spanish America, moved by the disaster, expressed its solidarity with Spain and the latter reduced the last traces of indifference. Thus arose “for the first time since independence, a common yearning for unity, no longer political, but spiritual and cultural”.

Rafael Altamira was the first to demonstrate in 1898 that the history of Spain was unintelligible without that of America and that Spaniards and Latin Americans shared feelings and values specified in what is called “Hispanic modality”.

Illustratively, in his American Letters (1889), Juan Valera to the president of Ecuador emphasizes the “unity of civilization and language, and to a great extent of race as well, persists in Spain and in those Republics of America, in spite of their emancipation and independence from the metropolis.”

Valera, defending the place of Spain and the Hispanic in America, added to the idea of hispanidad the concept of prolongation of the Hispanic historical reality and personality in the American republics, without denaturalizing their own mestizo identity or the common heritage that made them universal; that is to say, the unity of blood, language and culture.

For Menéndez Pelayo, his idea of Hispanic culture can be interpreted from “To the Reader” and “General Warnings” of his History of Spanish-American Poetry (1911), the first history of American poetic production, framed in the cultural and aesthetic context of each of the countries, from the vice regal era to the mid-19th century. This text derived from the Antología de poetas hispanoamericanos, a project commissioned to him by the Real Academia Española in 1892, with two motives:

1) in honour of overseas Spain during the celebration of the IV Centenary.

2) to counteract the ignorance and lack of interest of Spaniards in Spanish America and its poetry.

His anthology was therefore, as Lohmann saw it: “a permanent act of Hispano-American fellowship”; with it he “gave backbone and channel to the spiritual content of Hispanidad (…) in order to re-establish the originality of the Spanish tradition transplanted to America”.

In conclusion, through his writings, Menéndez Pelayo institutionalized the idea of Hispanidad as a “spirit of fraternity”, of integration and alliance of the nations of the Hispanic race, by virtue of the extension of its Castilian language, Catholic religion, Roman law and Latin civilization, implicitly honoured in the Commemorations of the IV Centenary.

For him then, “the peninsular and the American were all one; their essential principles, common, and interdependence an irrevocable fact. America was the vital prolongation of Spain”.

Unamuno‘s interest in Spanish America grew as he gradually identified “the characteristics that distinguished Spain from its European neighbours.” For him Spain and Spanish America formed a community of ethnically and politically dissimilar nations, whose historical and cultural character was due to the unity, equality, justice and universality of their Hispanic spiritual heritage, based essentially on the Spanish language. Unamuno called this community, in 1909, Hispanidad. He complained, therefore, of the lack of interest of Spaniards in American issues, even though Spain should find answers and encouragement for itself in its former colonies. He agreed in this sense with Rubén Darío and Altamira.

“We Spaniards must finish losing everything that is enclosed in the mother country and understand that to save the Hispanic culture it is necessary for us to start working with the American peoples and receiving from them, not only giving to them”.

In short, without remaining in the mere linguistic factor, he pointed out the Spanish language as the decisive constitutive force of the spiritual, literary, socio-political and historical unity between Spain and America; thanks to this language, Hispanidad was to be understood as fraternal exchange, mutual interest and mutual knowledge.

Thanks to the philosophical and literary contributions of these authors, it can be affirmed that “The construction of Hispanidad is the mutual work of Spaniards and Hispanic Americans who have managed, through individual efforts and intentions, to crystallize a coherent, rational result, of affective feelings not exempt from criticism. In short, communication paths to the construction of the building of this identity, using the not inconsiderable foundations of a vital, social and ideal community of more than three centuries (Hernández 2012).

National and international celebrations

The celebration of October 12 has for many years cultivated diplomatic sociability during the meals and receptions offered. Outside Spain, embassies have encouraged its celebration. As has been the custom since the 1950s, receptions for Ibero-American diplomats are held in London, Paris, Rome and Lisbon.

As an example of the importance of the celebration of this date, the commemorative display for October 12th, 1963 was especially orchestrated in the United States. So much noise was generated by the Spanish diplomacy for October 12th in some American cities that even President John F. Kennedy joined in the remembrance, receiving in the White House gardens associations of Spanish emigrants and their descendants.

Due to its diplomatic and cosmopolitan character, the celebration defined the state of international relations and Spain’s place in the world throughout the 20th century.

Since its institutionalization in 1918, its staging has been a sophisticated state ritual that demarcated honour, distinction and elitism. Every October 12th is a space for public relations among diplomats, visitors from foreign governments and, occasionally, professionals linked to education, local political management, tourism and other professional sectors. During this social atmosphere, personal relationships have been established and informal sociability is practiced, which has generated a multitude of images and opinions. The festival has been a microcosm of Ibero-American cosmopolitanism that sets in motion international projects for national regeneration.

Finally, to understand the participation of the Armed Forces in the Fiesta, we refer to RD 862/1997, of June 6, which regulates the commemorative events of the Spanish National Day. The regulation transfers to October 12th the events that had been taking place on the Day of the Armed Forces (FAS), on the feast of Saint Ferdinand, considering that it will contribute to identify the Armed Forces with the society they serve.

It also provides that on this day military personnel will dress in full dress and, within the Ministry of Defense, there will be a general adornment of buildings and ships. In addition, it determines that a military parade and a solemn homage of respect and exaltation to the Spanish Flag, ensign of the Fatherland and symbol of its unity and national coexistence, will take place.

The National anthem is 251 years old

In this context, it is important to highlight the Spanish National anthem, which is 251 years old. We have one of the oldest national anthems in Europe. Declared March of Honour in 1770 by Charles III, the same King who held the contest that served to choose the design of our current flag in 1785.

Although officially its author is unknown, its origin is in a military touch “the Grenadier march”, which appears in the “Book of ordinance of the military touches of the Spanish Infantry” dated 1761 and in the name of Manuel de Espinosa, so it is to this who is attributed the authorship of the hymn, although unofficially.

The grenadiers were at that time the heroes of the moment and belonged to the elite corps of the army. Due to the prestige they possessed, they were in charge of accompanying the kings in their parades.

Carlos III decided to declare this march as “Marcha de Honor” in 1770, and the Spanish citizens liked it so much that it soon became popularly known as “Marcha Real” because it was always played in all the events attended by the monarchs.

The “Royal March” has been the anthem of Spain ever since, with the exception of the Liberal Triennium (1820-1823) and the Second Republic (1931-1939), the only periods of time in which the current version of the anthem was replaced by the “Hymn of Riego”. However, after the civil war, it was again established as we know it today. The most precise regulation was made in 1997, the year of the full acquisition of the author’s rights by Colonel Grau, director of the “Banda de la Guardia Real” (Royal Guard Band) who gave his rights for free.

In spite of all the years of validity of the hymn, there have been several attempts to change the march for a new version as, for example, through the contest that General Primo organized in 1868 in search of a new melody, without success. None of the five participating versions was of the quality that the hymn deserved.

In summary, October 12 has a meaning of celebration and pride in the homeland for most Spaniards that must be cultivated and celebrated for the inheritance of future generations.

Bibliography, readings and complementary resources:

- Alvarez, Angel. 1950. El pensamiento de Unamuno sobre Hispanoamérica. Madrid: Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos

- Alvarez, Rafael. 1895. El porvenir de la raza. Revista Contemporánea. Julio-Septiembre

- Laín Entralgo, Pedro. 1999. Historia de España Menéndez Pidal. Madrid: Espasa Calpe

- Real Academia Española. 2001. Diccionario de la lengua española. Recuperado de http://lema.rae.es/drae/

- Valera, Juan. 1890. Nuevas cartas americanas. Madrid: Fernando Fe.

- Roberts, Stephen. 2004. “Hispanidad”: El Desarrollo de una polémica noción en la obra de Unamuno. Cuadernos de la Cátedra Miguel de Unamuno.

Web resources:

- www.dialnet.unirioja.es/

- www. dspace.unia.es/handle/10334/105

- www.bne.es/es/Catalogos/HemerotecaDigital/

- www.protocoloimep.com /articulos/la-fiesta-nacional-y-sus-125-anos-de-historia/