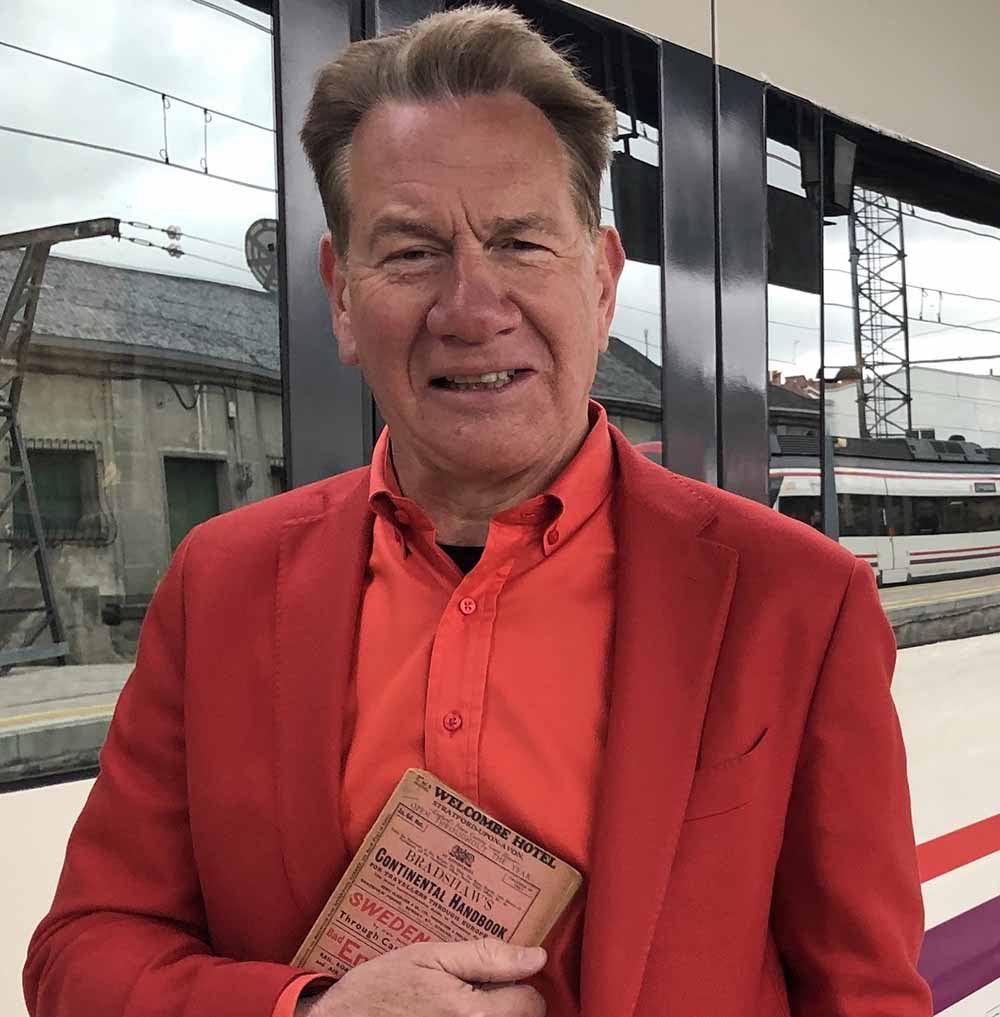

FHB Interview with MICHAEL PORTILLO

In this interview we are going to get to know better a British and Spanish man – he has both passports -, capable of living politics with positions in the governments of Margaret Thatcher and minister with John Major, being a member of the House of Commons and a solvent aspirant to the leadership of the British Conservative Party, and later to become one of the most popular travel and documentary journalists in the world. There must be so many stories to tell on his agenda…

ISABEL AIZPÚN

Madrid, October 2020

Were you Margaret Thatcher’s dolphin?

My parents were both on the Left in politics, and as a young person I supported the British Labour Party. But as I was leaving university, Margaret Thatcher became leader of the Conservative Party. She was different from others, because she knew what she wanted to acheive. I cannot tell you how rare that is in a leader; and she had the energy to succeed. I joined the Party’s research department, and at the 1979 general election (which she won to become prime minister for the first time) I met her each morning to prepare her for her press conference. After I was elected to the House of Commons, she promoted me to several ministerial positions, although I joined the cabinet only under her successor, John Major. She certainly gave me opportunities and I was proud to think of myself as one of a group of junior ministers whose loyalty to her was not in doubt. In November 1990, when she was challenged for the Party leadership, I found myself alone with her, urging her not to resign, after she had achieved a disappointing result in the ballot. Sadly, she stepped down, none the less.

What attracted you to that personality to follow her and enroll in her policies?

Margaret Thatcher took power when Britain was in a pitiful state. The public finances were in a mess, trades union leaders had enormous destructive power, and Britain was despised as the sick man of Europe. Her policies and personality revived the country’s morale and the trades unions were thwarted in their anti-democratic efforts. The partnership of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan helped to bring an end to the Soviet Union, and enabled the liberation of eastern Europe from communism.

In those years, Michael Portillo had already shown his Spanish and British origins because his father Luis Gabriel Portillo, from Ávila, professor at the University of Salamanca, went into exile in Oxford in 1939 and there he met his mother, Cora Blyth, who cared for Basque children refugees from war. With what you have lived in your family since then, what draws your attention to the differences and affinities between British and Spanish?

Spanish people have many enviable personal virtues. The family flourishes more in Spain than in Britain, and the generations mix and understand each other better in Spain. Britain’s strengths are institutional. The fact that British democracy and the rule of law survived throughout the twentieth century, while they were extinguished by fascism and communism in most of Europe, gives Britain a remarkable stability.

At least you can say that you have had two lives so far. Surely you will have had to measure yourself with the media in the first one and now, in a way, you are part of them… How was that transition?

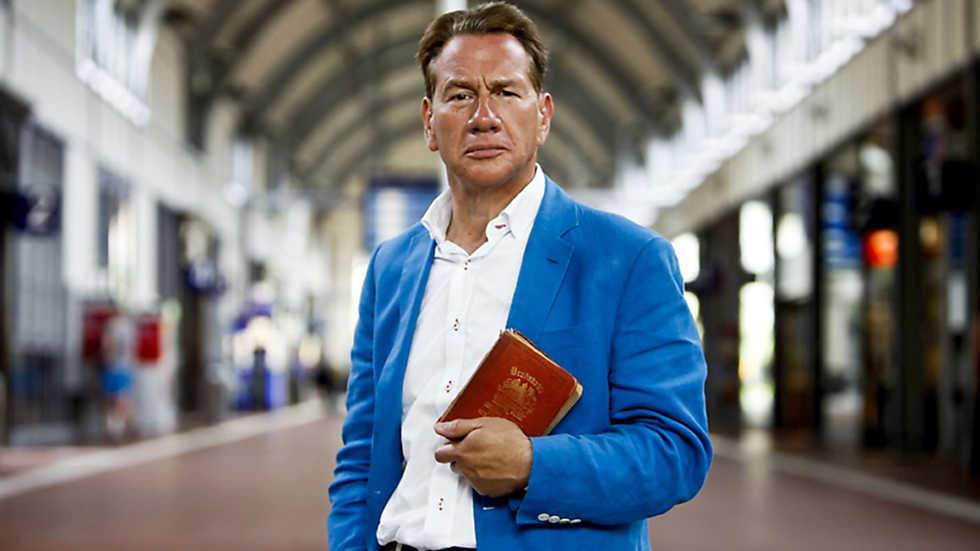

I made the transition out of necessity, because I needed to work after I lost my seat in parliament. Some of what I have done since is to write or broadcast political commentary, so that is not a big step from a career in politics. But I am now best known from presenting documentaries. When I do so, I have a concept of history which I wish to share with you, a story that I wish to tell you, and to convince you that it can be believed. So there are tools that can be transferred from politics to television.

Now you can tell History, Politics or Literature through travel. What do you like to highlight about the places you know?

For me the journeys are not about trains, but about getting off the train. In each place I want to know, and talk about, what happened here. It may be an old factory, the site of a battle, the childhood home of a statesman, a gallery housing a seminal painting or the birthplace of a revolution…

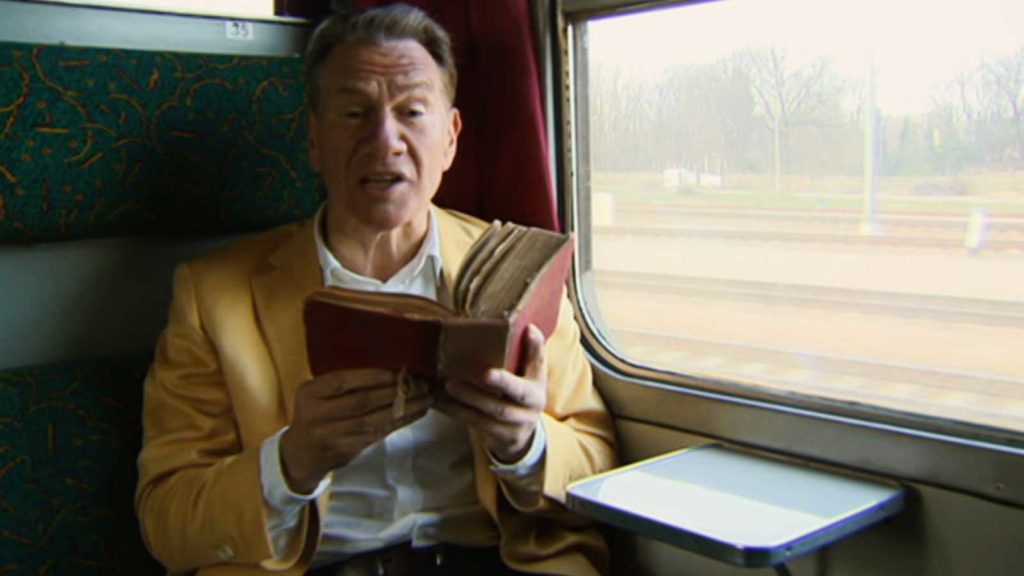

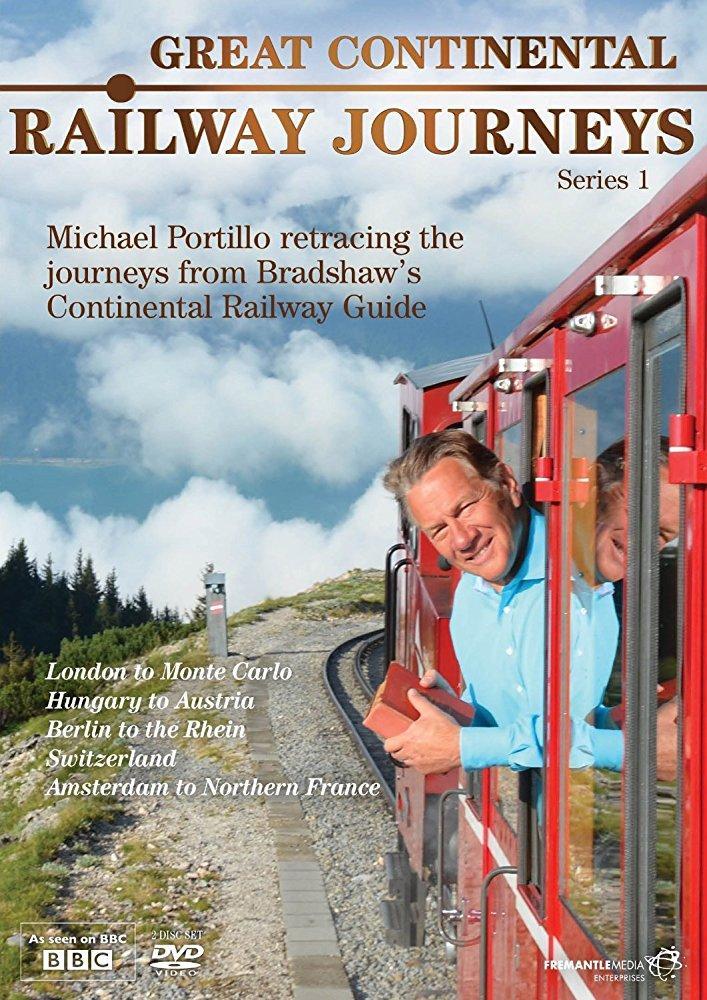

In Britain there has traditionally been a high appreciation of travel, long travel, learning for the traveler. After 300 trips in 33 countries with the BBC’s Great Continental Railway Journeys, which ones have impacted you the most? What trip has been the most enjoyed telling you?

Making such choices is not easy, and also risks giving offence! I will pick out two. One is Spain, not surprisingly. In fact, a rail journey through Spain that I filmed back in 1998 (for a previous series which had a different presenter each week) was the origin of the Great British and then Great Continental Journeys. The most recent series of Continental Journeys returns to Spain and to the story of my father Luis in the civil war, as my 1936 Bradshaw’s guidebook takes me from Salamanca (and Luis’s account of Miguel de Unamuno’s last lecture, to the Telefonica in Madrid where Arturo Barea and Ernest Hemingway endured heavy shelling, to the trenches where George Orwell fought above Huesca, where I am in the company of his son.

I will also pick out Georgia, a former republic in the Soviet Union. The people are so welcoming, they are so brave against their big Russian neighbour, their Christianity is so intense and enduring, their unique alphabet has produced such rich literature; and this people is so friendly and in love with wine-making, they sing so beautifully and live in stunning mountain scenery.

I do not think that the British are exceptional travellers. I do not forget that the Roman Emperors Trajan and Hadrian were from present day Spain. Colon sailed from Spain with royal Spanish patrons. The stories that move me most are those of liberation. In Cracow we looked at how the election of a Polish Pope helped to bring down the Iron Curtain. The choirs of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania joined hands in an enormous human chain that physically linked their capitals to bring an end to Soviet dominion. The people of France evoked the spirit of Joan of Arc (15th century heroine in the struggle against the English) to drive out the Germans in 1918 and 1944.

Is it wise to travel?

Of course it is wise to travel to learn about other nations, and if because of infirmity you cannot travel, please journey with me on your television screen.

Are you able to prepare a third life? To surprise us with a new activity after political life and that of the traveler?

Third life sounds too like tercera edad! I can say that I am contracted to make rail journeys for the BBC in 2020 and 2021, and I have just begun to present a new three-hour programme of debate and discussion, weekly on Times Radio.

As a politician and as a traveler you are surely an observer of the present time, if you could give advice to the Foundation to continue bringing British and Spanish closer, what would you advise?

The EU, including Spain, has to accept that Britain has left the EU. Because of the institutional strength that Britain has, which I mentioned, the British people did not yearn for, respect or accept European institutions in the way that Spanish people do. I believe that that is true even of most of those who voted (for cultural reasons) to remain. Britain was not happy in the EU, and the EU could not be very happy with us, because we did not want to travel to the same destination. Now that we are uncoupled, our relationship can be much easier, no longer polluted by insincerity.