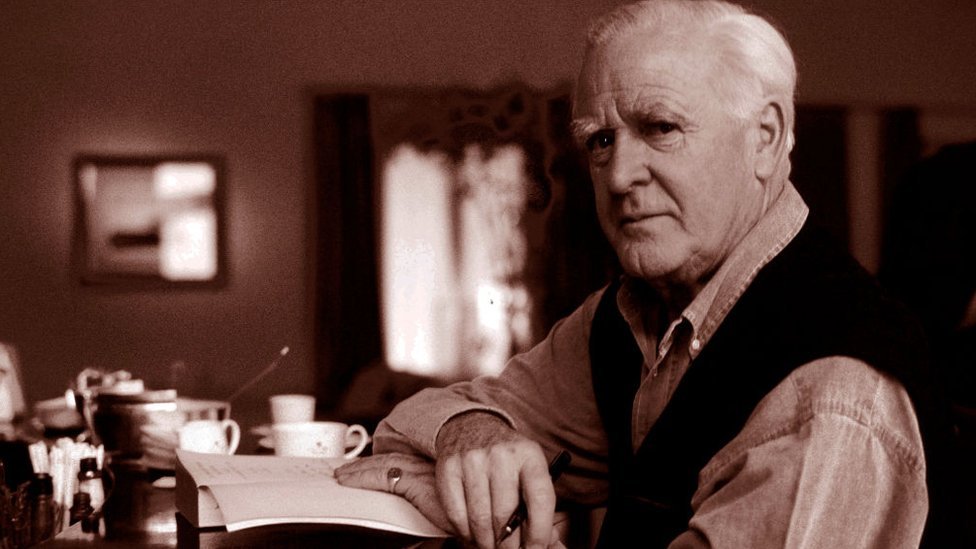

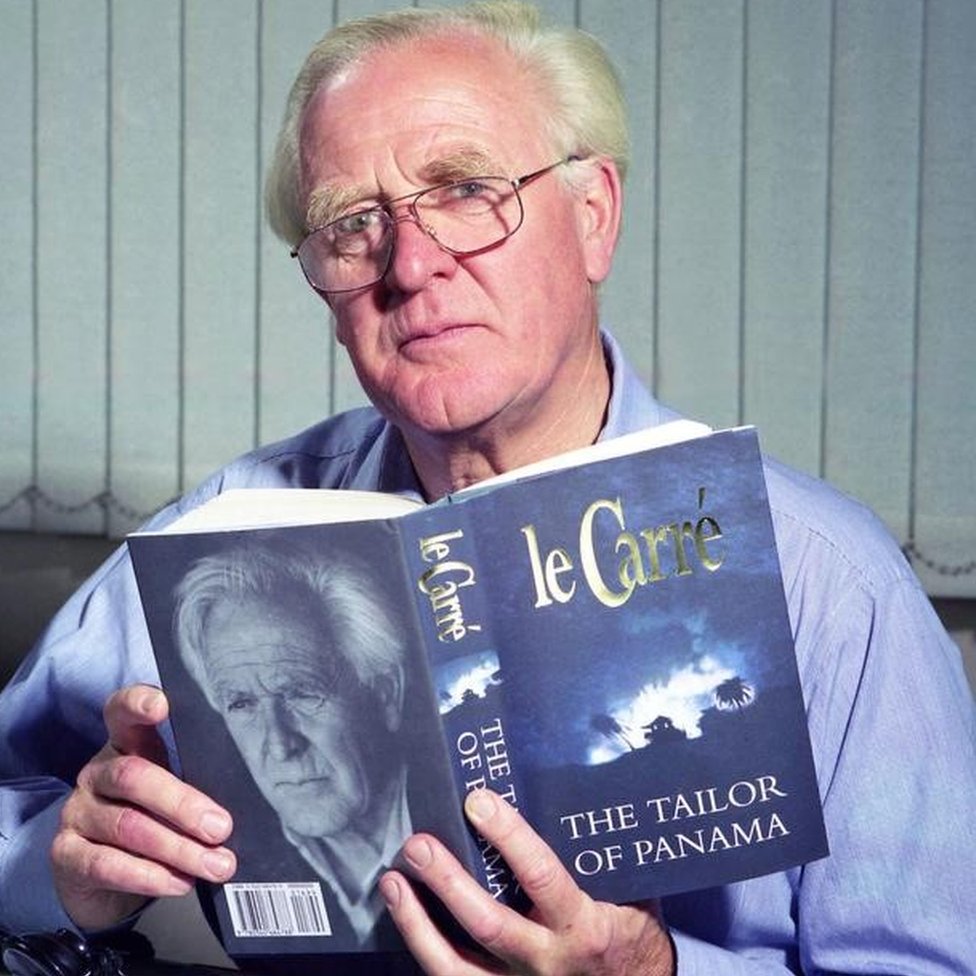

British espionage writer John le Carré has died aged 89, following a short illness, his literary agent has said.

The author of The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy died from pneumonia on Saturday.

Jonny Geller described him as an «undisputed giant of English literature» who «defined the Cold War era and fearlessly spoke truth to power».

«We will not see his like again,» he said in a statement.

Mr Geller said he represented the novelist, whose real name was David Cornwell, for almost 15 years and «his loss will be felt by every book lover, everyone interested in the human condition».

«We have lost a great figure of English literature, a man of great wit, kindness, humour and intelligence. I have lost a friend, a mentor and an inspiration.»

A statement shared on behalf of the author’s family said: «It is with great sadness that we must confirm that David Cornwell – John le Carré – passed away from pneumonia last Saturday night after a short battle with the illness.

«David is survived by his beloved wife of almost 50 years, Jane, and his sons Nicholas, Timothy, Stephen and Simon.

«We all grieve deeply his passing. Our thanks go to the wonderful NHS team at the Royal Cornwall Hospital in Truro for the care and compassion that he was shown throughout his stay. We know they share our sadness.»

The statement said his death was not Covid-19 related.

Several of le Carré’s 25 works were turned into films including The Constant Gardener, The Tailor of Panama and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, while the Night Manager became a succesful BBC television series.

His most famous character, George Smiley, who first appeared in Call for the Dead, has been played by actors including Rupert Davies, Alec Guinness and Gary Oldman.

What was the Cold War?

The decades after the end of World War Two in 1945 were dominated by political tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, along with their respective allies in the Western bloc and the Eastern bloc.

Both sides were armed with nuclear weapons, discouraging direct warfare because of the risk that both would be totally destroyed.

So until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the hostility played out in support for regional conflicts known as proxy wars, propaganda campaigns, psychological warfare and espionage – creating the inspiration for a generation of spy novels and films.

Paying tribute to le Carré, author Stephen King said in a tweet: «This terrible year has claimed a literary giant and a humanitarian spirit.»

And historian and novelist Simon Sebag Montefiore described le Carré as «the titan of English literature» and said he was «heartbroken».

Historical fiction writer Robert Harris said he was «one of the great post-war British novelists» and «an unforgettable, unique character».

Actor Oldman, who appeared in the 2011 film of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, said le Carré was «a very great author, the true ‘owner’ of the serious, adult, complicated, spy novel» and was «always a true gentleman».

Author Margaret Atwood tweeted that the Smiley novels were the «key to understanding the mid-20th century».https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.36.7/iframe.htmlmedia captionIn an interview last year, John le Carré talked about the conflict between personal and state obligation

Born as David Cornwell in Poole, Dorset, in 1931, he wrote under the pseudonym of John le Carré.

He studied at the university of Bern, in Switzerland, and then Oxford, before entering a career in undercover intelligence.

After teaching at Eton for two years he joined the Foreign Office, and was initially based at the British Embassy in Bonn.

During his time there he worked in the intelligence records department, giving him access to files with insights into the workings of the secret service.

He also wrote his first novel, Call For The Dead, which was published in 1961.

This meant the need for a pen name as Foreign Office officials were not allowed to publish books under their own name.

In 1963, his third novel, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, brought him worldwide acclaim and allowed him to take up writing full time.

Le Carré said his manuscript was approved by the secret service because they «rightly if reluctantly» concluded it was «sheer fiction from start to finish» but he said the world’s press took a different view, deciding the book was «not merely authentic but some kind of revelatory Message From The Other Side».

His career as a spy came to an end in 1964 after his name was one of many given to the Soviet Union by a double agent, an incident which inspired a plot line in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

Two things stand out about this prolific and hugely successful author.

Firstly, his novels were the very antithesis of the glamorous, racy world of James Bond as depicted by fellow author Ian Fleming.

Whether it was the grim reality of waiting hours for an agent to cross back into West Berlin in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, or the drab, grey world of Cold War MI6 that he describes in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, le Carré stripped away the glitz to reveal a world of fallible, flawed characters.

Secondly, there is his extraordinary longevity.

Le Carré, who spent a relatively brief period with MI6, published his first novel in the same year that the Berlin Wall went up: 1961.

Yet long after the Cold War ended, decades later, he went on to diversify into writing about the arms trade, Big Pharma and the so-called War on Terror.

On the few occasions I met him he seemed genuinely surprised at his own extraordinary success.

Le Carré turned down literary honours and a knighthood, saying in a 2017 US interview that he was «so suspicious of the literary world that I don’t want its accolades».

«And least of all do I want to be called Commander of the British Empire or any other thing of the British Empire,» he added, saying it was «emetic» or vomit-inducing.

He told CBS News’ 60 Minutes: «I don’t want to posture as someone who’s been honoured by the state and must therefore somehow conform with the state, and I don’t want to wear the armour.»

Le Carré described himself as «English to the core» but deplored what he saw as the aggressive nationalistic sentiment behind Brexit.

«My England would be the one that recognises its place in the EU. The jingoistic England that is trying to march us out of the EU, that is an England I don’t want to know,» he said.

Obituary: John le Carré

John le Carré was the pseudonym of the author David Cornwell, judged by many to be the master of the spy novel.

Meticulously researched, and elegantly written, many of his books reached a wider audience through TV and film adaptations.

Le Carré stripped away the glamour and romance that were a feature of the James Bond novels and instead examined the real dark and seedy life of the professional spy.

In the twilight world of le Carré’s characters the distinction between good and bad, right and wrong was never that clear cut.

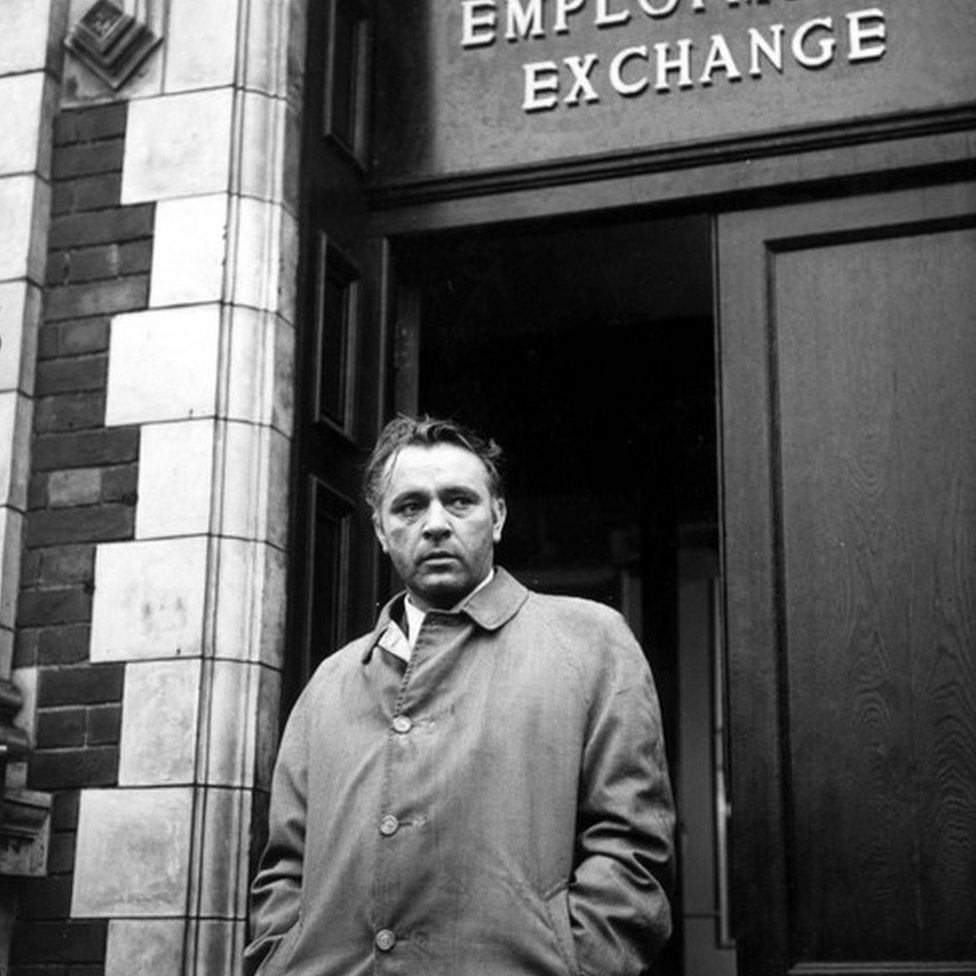

David John Moore Cornwell was born on 19 Oct 1931 in Poole, Dorset.

His father, known as Ronnie, was a fraudster, described by one biographer as «an epic con man of little education, immense charm, extravagant tastes, but no social values».

Those exploits gave the young Cornwell an early introduction to the arts of deception and double-dealing which would form the core of his writing.

His mother walked out when he was five and the young David invented the fiction that his father was in the secret service to explain his many absences from home.

After attending Sherborne School he went on to the University of Berne to study foreign languages.

He did his military service in the Army Intelligence Corps, running low grade agents into the eastern bloc before going to Lincoln College, Oxford, where he gained a BA.

After teaching at Eton for two years he joined the Foreign Office, initially as Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Bonn.

During his time there he worked in the intelligence records department and began scribbling down ideas for spy stories on his trips between work and home.

‘Excellence in his profession’

His first novel, Call For The Dead, appeared in 1961 while he was working for the intelligence service.

He adopted the pen name, John le Carré, to get around a ban on Foreign Office employees publishing books under their own name.

The story introduced characters who would reappear in subsequent novels including his most famous creation, George Smiley.

«The moment I had Smiley as a figure, with that past, that memory, that uncomfortable private life and that excellence in his profession, I knew I had something I could live with and work with.»

Le Carré’s career as a spy ended when he became one of many British agents whose names were given to the Russians by the traitor Kim Philby.

Philby, who defected to Moscow, later became the inspiration for the mole «Gerald» in Tinker Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

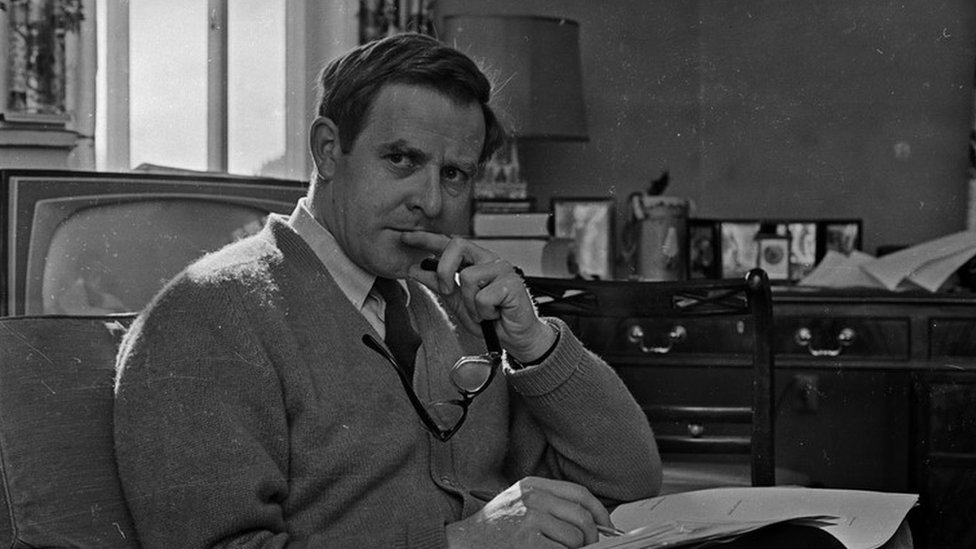

It was his third novel, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, which cemented his reputation and allowed him to take up writing full time.

Fallible human beings

Published at the height of the Cold War it challenged the perception held by many of his readers, that western spies were above the dirty tricks practiced by their counterparts in the east.

The novel won the Golden Dagger award for crime fiction and was turned into a memorable film with Richard Burton in the role of the disillusioned spy, Alec Leamas.

In direct contrast to Ian Fleming’s romantic James Bond fantasies, le Carré portrayed his spies as fallible human beings, fully aware of their own shortcomings and those of the systems they served.

Le Carré believed that The Looking Glass War, published in 1965, was his most realistic description of the intelligence world in which he had worked, and cited that as the main reason for its lack of success.

The follow up, A Small Town in Germany, was set in Bonn, where le Carré had worked, and warned of the dangers posed by a revival of the far right in German politics.

In 1971 he published an autobiographical novel The Naïve And Sentimental Lover, based on the break up of his first marriage to Alison Sharp.

His character, George Smiley, re-emerged in his trilogy, Tinker Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Honourable Schoolboy and Smiley’s People.

Well-hidden expertise

The books took his readers deep into «the circus» with jargon such as «honey trap», «mole» and «lamplighter» becoming common parlance.

They also raised serious questions about the lengths to which even democracies would go to preserve their own secrets, something that exercised le Carré greatly.

He argued that in a world where official secrecy is all-pervasive, the spy novel performed a necessary democratic function. To hold up a mirror, however distorted, to the secret world and demonstrate the monster it could become.

Ironically, he delighted in maintaining secrecy in his own personal life, refusing for many years to even acknowledge that he had been a spy himself.

He jealously guarded his privacy, travelling alone and incognito when he set off to research his novels.

For years he refused invitations to do any interviews, maintaining that what he wrote was «the stuff of dreams, not reality» and he was not, as the press seemed to imply, an expert on espionage.

As the Soviet bloc began to implode le Carré switched his attention to the conflict in Palestine with his 1983 novel The Little Drummer Girl.

Political engagement

Three years later he finally managed to exorcise the memory of his father with the publication of A Perfect Spy, which many critics consider his most accomplished work.

The life of the spy, Magnus Pym, is dominated by memories of his father Rick, a rogue and con-man whose character is firmly based on Ronnie Cornwell.

In 1987, after years of being ostracised by the Soviet authorities, le Carré was given permission to spend two weeks in Russia, as a guest of the Soviet Writers’ Union.

It was rumoured that the wife of the Russian leader, Raisa Gorbachev, was a fan of le Carré’s books and that she had a hand in gaining the necessary Kremlin approval for the trip.

His output continued to be prolific with a 1989 novel, The Russia House, marking the end of the Cold War, and the reappearance of George Smiley in The Secret Pilgrim in 1991.

The 1996 novel, Tailor of Panama was inspired by the Graham Greene story, Our Man in Havana, while The Constant Gardener, published in 2000, saw him switch his attention to corruption in Africa.

In 2003 he joined a number of writers attacking the US led invasion of Iraq in an essay entitled, The United States of America Has Gone Mad.

«How Bush and his junta succeeded in deflecting America’s anger from bin Laden to Saddam Hussein is one of the great public relations conjuring tricks of history», he wrote.

His remarks probably contributed to accusations of anti-American bias in his 2004 book Absolute Friends, an examination of the lives of two radicals from 1960s America, coming to terms with advancing age.

In 2006 his 20th novel, Mission Song, detailed the sometimes complex relationships between business and politics in the Congo.

Notably self-disparaging about his own achievements he consistently refused honours, insisting that there would never be a Sir David Cornwell.

«A good writer is an expert on nothing except himself», he once said. «And on that subject, if he is wise, he holds his tongue».