Stephen Mulvey

December 2020

More has been written about Thomas Becket, the archbishop hacked to death in Canterbury Cathedral exactly 850 years ago, than any other non-royal English person of the Middle Ages. And yet it seems it’s still possible to discover new things about his remarkable life.

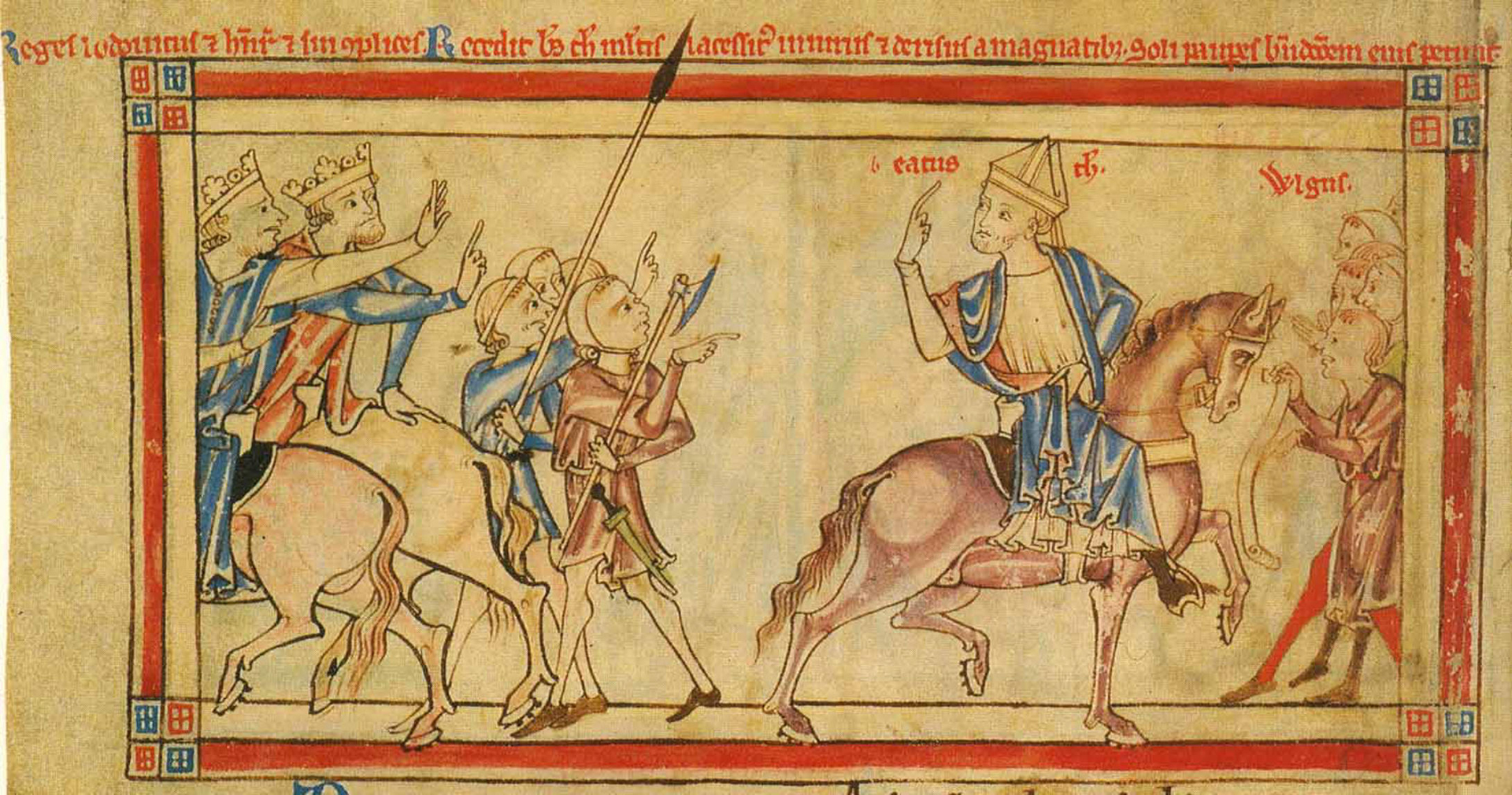

Before dawn on 14 October 1164, Thomas Becket found an open gate in the city walls and rode out of Northampton with a servant and two guides, the sound of their horses’ hooves masked by high wind and driving rain.

The archbishop was making a run for it after a week on trial in Northampton Castle. The initial charge had been a minor one, but King Henry II had added new and increasingly serious accusations, and a verdict of treason was looking likely.

Becket headed north, making it to Lincoln in two days, then put on the rough, dark woollen tunic of a local religious order, adopted the name Brother Christian, and turned south into the wilderness of the fens. His companions were genuine lay brothers, able to lead him through the marshes and waterways to isolated hermitages and priories, where he would be able to plan his next moves. Had he been caught, the leading Becket expert Prof Anne Duggan says, the king could have chosen any punishment he liked – castration, blinding, even death.

But Becket wasn’t caught.

He made it, ultimately, to Kent and was rowed from there to France in the first days of November.

In exile he would need money, so before leaving Northampton, Becket had secretly sent his closest confidant, the scholar Herbert of Bosham, to Canterbury, to gather as much as he could and to take it to the Abbey of St Bertin, near Calais. But there was also one other thing he wanted Herbert to find – a certain little book.

«The implication is that it was a book that was very important to Becket, and that Herbert would know what it was,» Anne Duggan says.

«It’s quite interesting that he doesn’t tell us – so there is a mystery there. It wasn’t a law book, it wasn’t a gospel, it was a little book – a codicella.»

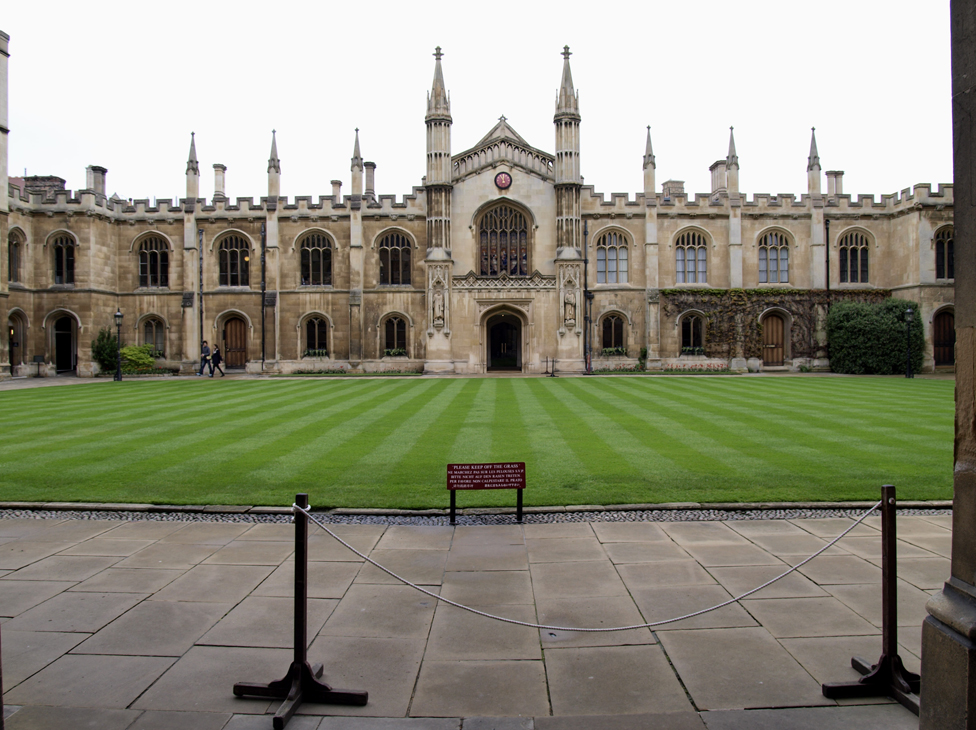

In the summer of 2014, Dr Christopher de Hamel, then librarian of one of the smallest Cambridge colleges, invited to lunch a medieval historian, Dr Eyal Poleg. Over coffee, de Hamel mentioned that he’d always thought it was odd that while any fragment of a saint’s clothing had been regarded in the Middle Ages as a holy relic, saturated with the Holy Spirit and capable of working miracles, the saint’s books were almost never regarded as such.

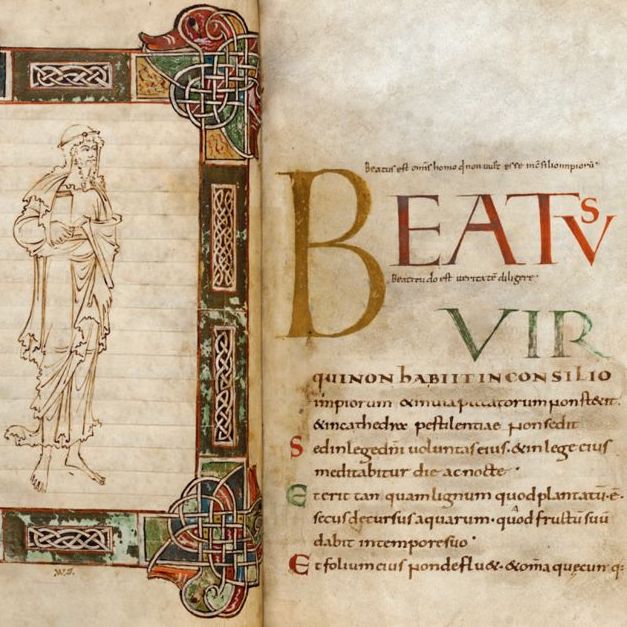

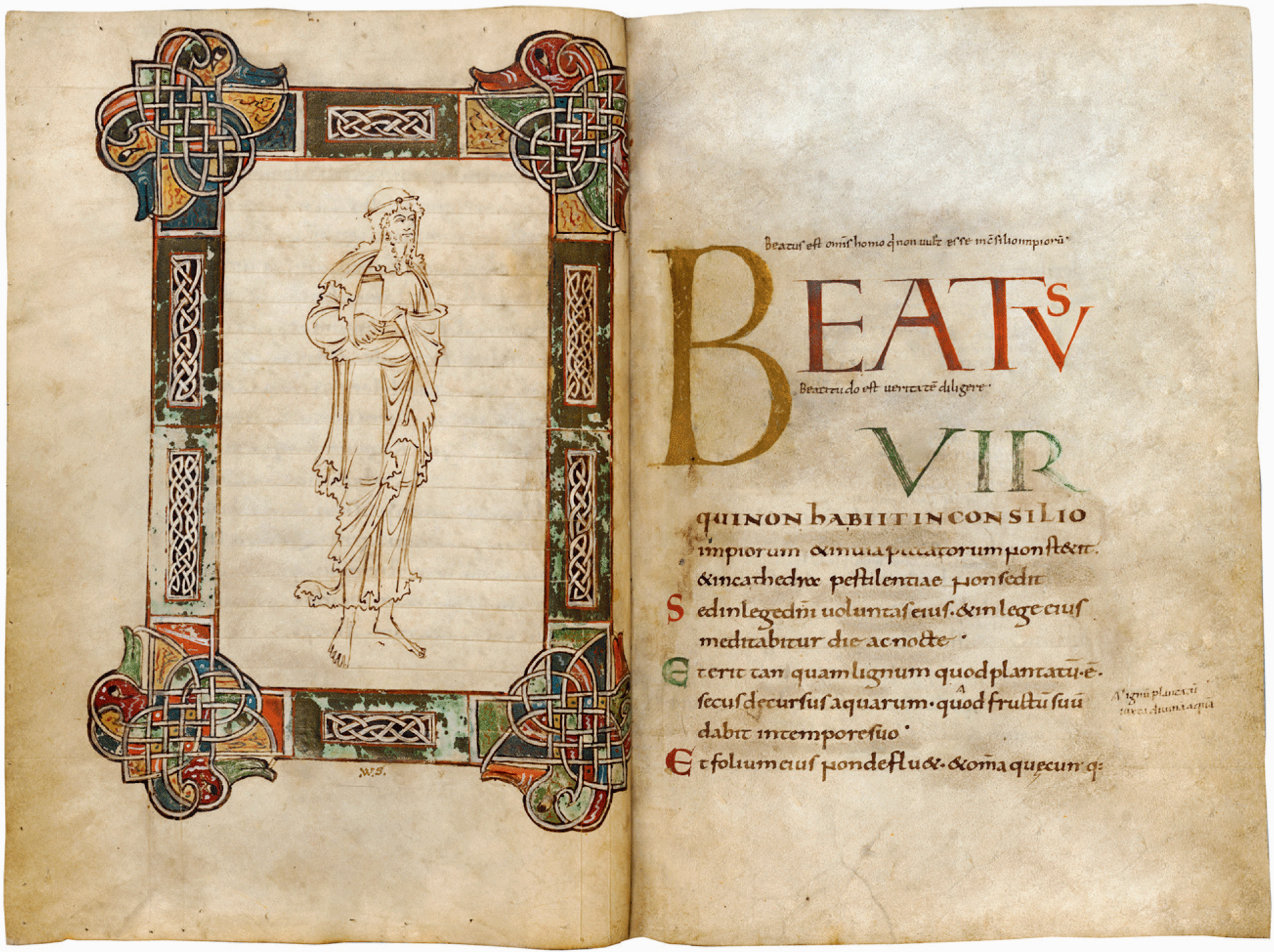

De Hamel says Poleg said he knew of a counterexample and, tapping on his laptop, called up a list made in 1321 of treasures held in Canterbury cathedral. In Latin he read out loud: «Item, a binding with the psalter of St Thomas, bound in silver gilt, decorated with jewels…»

As he heard these words, de Hamel says he had «one of those sudden heart-stopping shivers of recognition that make our lives as historians worthwhile». He’d read them before – in one of the manuscripts he looked after in the Parker library, a collection bequeathed to Corpus Christi College Cambridge by a former archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, in 1574.

The inventory surely had to be referring to the same book.

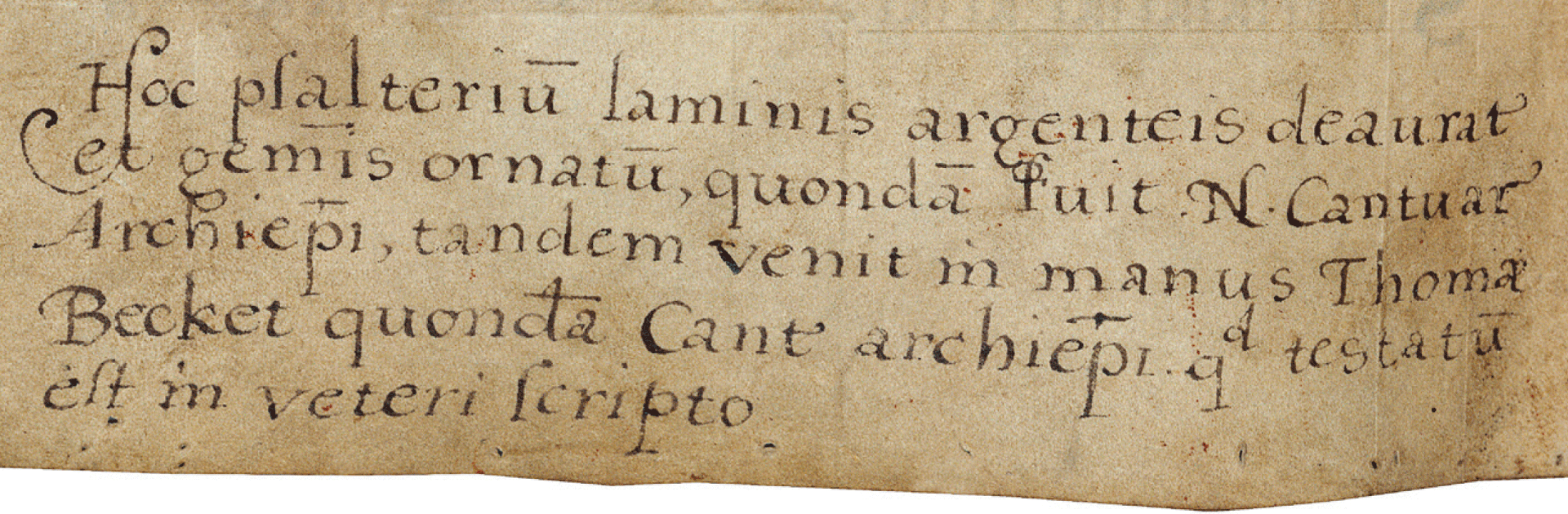

De Hamel and Poleg abandoned their coffee and rushed across the 200-year-old «New» Court, to the library. De Hamel brought from the vault a 1,000-year-old psalter – a book of psalms – and showed Poleg a note added to one of the final pages about 500 years ago, in the time of Matthew Parker.

«This psalter, in boards of silver-gilt and decorated with jewels,» it began, «was once that of N, archbishop of Canterbury [and] eventually came into the hand of Thomas Becket, late archbishop of Canterbury, as is recorded in the old inscription.»

Up until this moment the note had been taken with a pinch of salt – «almost certainly a complete fiction» was one recent assessment – but suddenly it was believable. The monks of Canterbury in 1321 certainly seemed to believe it.

One reason for scepticism had been the psalter’s absence from an early 14th Century inventory of the cathedral’s manuscripts, a list that does include about 75 other volumes that had once belonged to Becket, along with the shelf numbers where they were kept in a passage way off the cloisters. (It’s still a storage area today, de Hamel notes, where vergers keep their bicycles and gardeners their watering cans.)

But this could now be explained: the psalter wasn’t kept with the other manuscripts, but in a store room for valuables, or on the shrine of St Thomas – as Becket became within three years of his murder on 29 December 1170.

De Hamel and Poleg gazed at the 8in-by-6in manuscript «trembling with excitement», de Hamel writes in a short book published earlier this year, The Book in the Cathedral: The Last Relic of Thomas Becket. There was no jewelled Anglo Saxon silver-gilt binding – this would have been torn off and melted down during the Reformation, but here was a book, de Hamel now felt, that was surely a lost holy relic of the Middle Ages.

As someone who has been familiar with Becket’s manuscripts since the 1970s, de Hamel was aware of a curious habit of the Canterbury monks of that era: they took the description of each book in the inventory and copied it on to the flyleaf or the first page of the book itself.

The front flyleaf of the psalter in front of de Hamel and Poleg had long been missing. But the Elizabethan note appeared to be a version of it, judging from the final phrase – «as is recorded in the old inscription». Perhaps in the 16th Century it was already hard to read, or the flyleaf was loose? That would explain why someone might have copied it on to a different page. And as Henry VIII had ordered the obliteration of the cult of St Thomas of Canterbury not long before, it was understandable that the reference to «St Thomas» had been changed to «Thomas Becket, late archbishop of Canterbury».

While the match between the entry in the 1321 inventory of cathedral relics and the note in the psalter was exciting, the note’s wording also contained a puzzle.

The book was «once that of N, archbishop of Canterbury [and] eventually came into the hand of Thomas Becket», it says. So who was N?

There is only one earlier archbishop whose name begins with N – Nothelm, in the early Eighth Century. And there is no way, de Hamel says, that this manuscript dates from that period. Judging from its style, it’s generally thought to have been made in Canterbury around 1000.

But de Hamel had an idea – perhaps the Elizabethan who annotated the psalter had mistaken the medieval AE – a combination of A and E – for an N? Sometimes they can look similar, he points out.

As it happens, the first two archbishops of the 11th Century both have names beginning with AE – Aelfric and Aelfheah (commonly known as Alphege) – and de Hamel argues that the psalter belonged first to one and then the other.

There are clues that point towards this conclusion, he says, including two curious additions to the text.

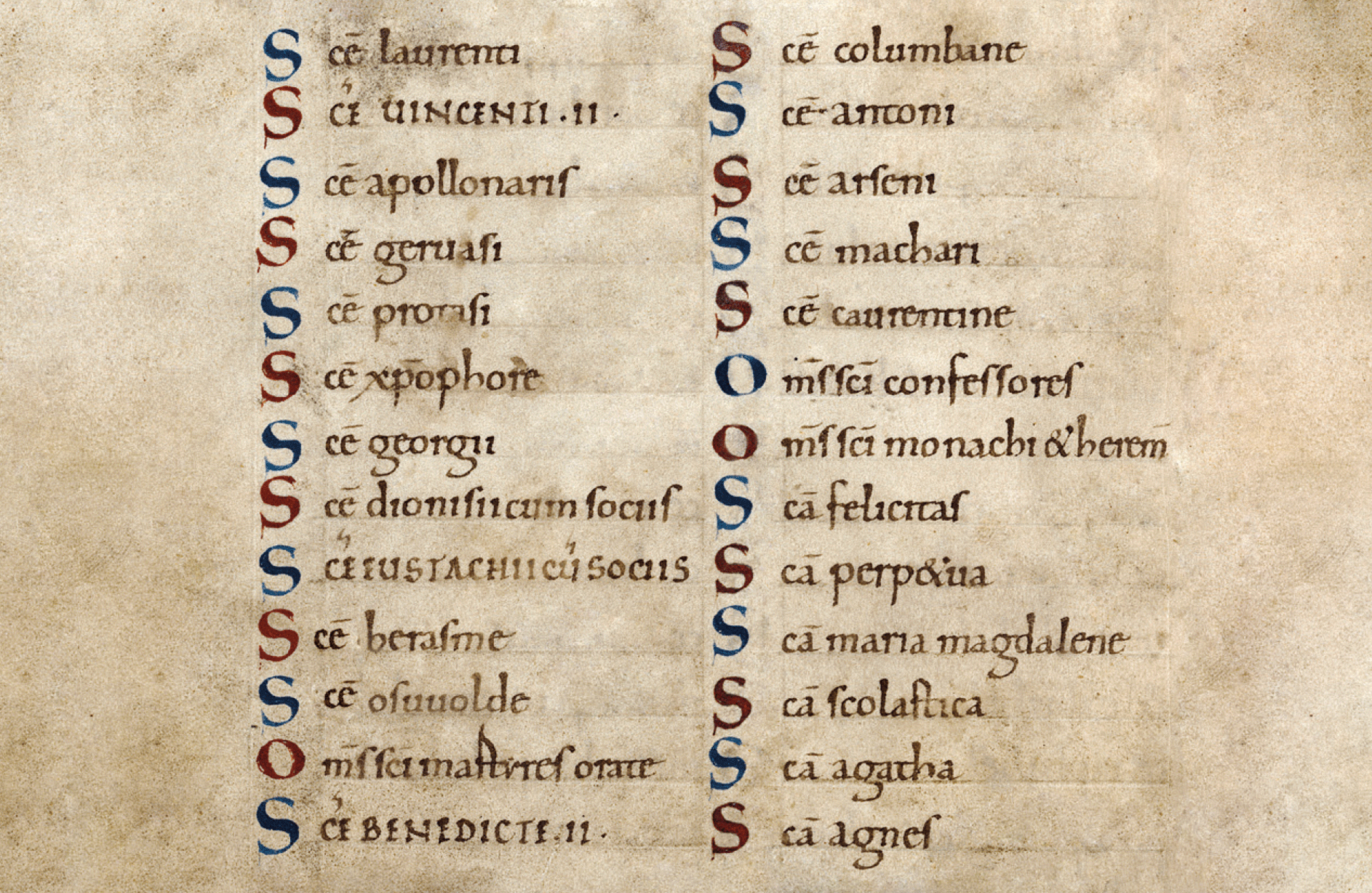

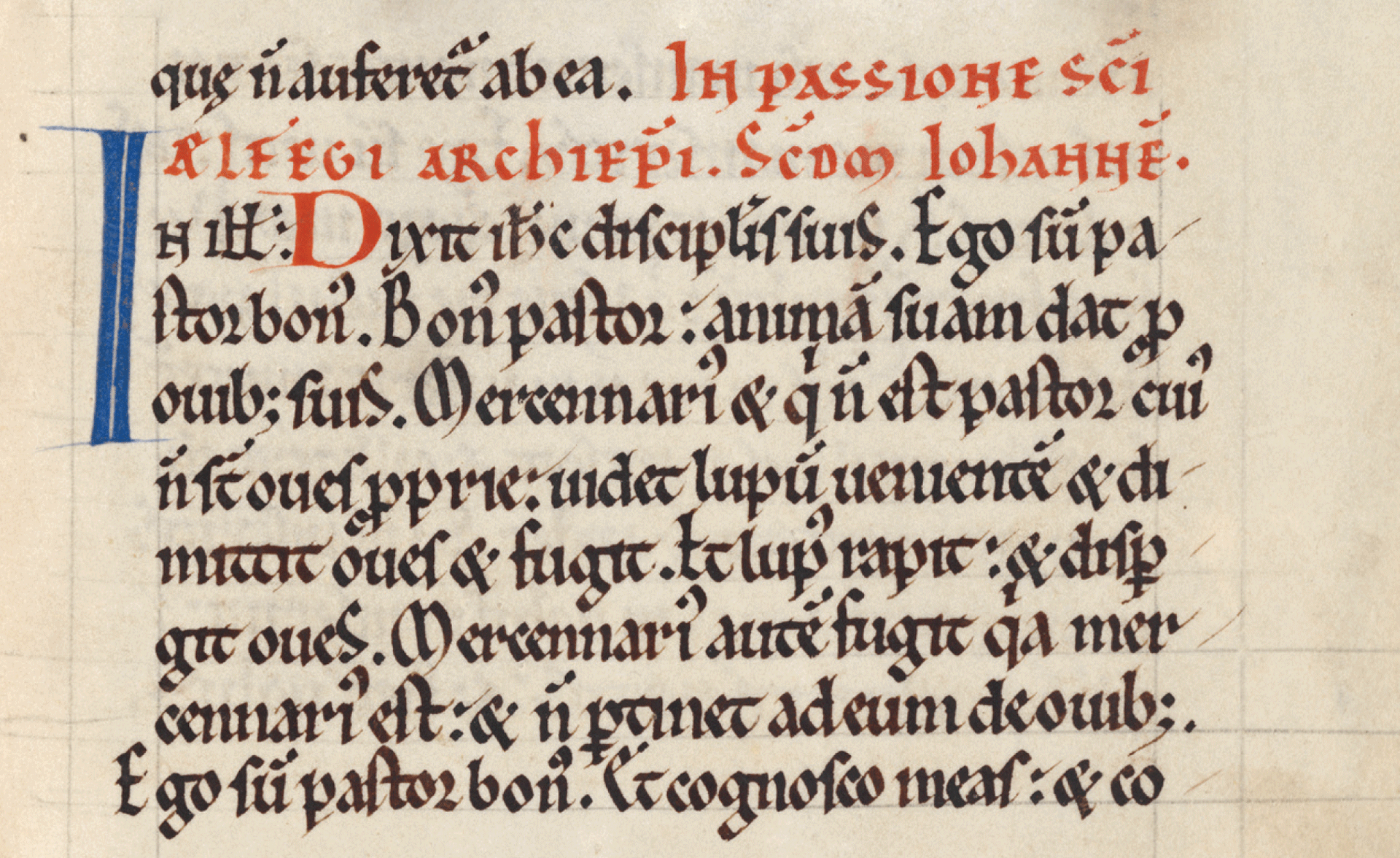

One is a litany of saints added to the end of the book, at roughly the same time the rest of the book was made, in which the names of two minor saints, Vincent and Eustace, appear in capital letters. This has previously been taken to suggest a connection between the psalter and the abbey of Abingdon, on the River Thames south of Oxford, which held important relics of both saints. De Hamel now suggests it is because the book belonged to Aelfric, who had been a monk at Abingdon, and possibly abbot, before he became archbishop in 995.

The second addition consists of religious texts to be read in memory of Alphege, archbishop from 1006 to 1012, when he was beaten to death by Danes at Greenwich. The simplest explanation for this, de Hamel argues, is that the psalter belonged to Alphege and became associated with his cult after he was canonised in 1078.

Alphege is recorded as joyfully reciting the psalms while in Danish captivity. Could it be, de Hamel asks, that he was holding this book when martyred? That would certainly have made it a relic in the eyes of the medieval church, he says, justifying the jewelled silver-gilt binding.

So there are now two candidates for the N mentioned in the inscription – Aelfric and Alphege.

Alphege appears to have been particularly important to Becket, who «in some way adopted Alphege as a patron saint» de Hamel says. Becket’s sermon in Canterbury Cathedral on Christmas Day 1170, just days before he was murdered, was on the death of St Alphege. And according to two contemporary accounts of the archbishop’s death, one by an eyewitness, his final words were to commend his soul into St Alphege’s care.

When de Hamel told this story in a lecture to the Society of Antiquaries of London in 2017, Anne Duggan was in the audience, and asked a question about the «little book» she had long wondered about.

In his biography of Becket, Herbert of Bosham says the archbishop told him «to take care of a particular book of his, lest when his flight was known to other people, it might be destroyed in the plundering» (using the translation in de Hamel’s book). He goes on to say that although Becket was «rightly indifferent to possessions» – actually he was renowned for his extravagance – «there was at least one little book that he cared about».

The psalter could have been it, Duggan suggested.

De Hamel can be seen on the video of the lecture listening with wide eyes and open mouth. «I feel a shiver going down my spine,» he says. Becket was probably already thinking about martyrdom, he adds, and the «evocative association with this martyr’s book must have mattered to him enormously».

In his book, he comments: «It may have been his most intimate possession. He probably took it to bed.»

Drawing on his deep knowledge of medieval manuscripts, de Hamel tells a gripping tale, extrapolated from tiny clues. But is it true?

«I wasn’t there when Becket died,» he tells the BBC, «and all the narrative constructed here [in the book] is like a detective story drawing on multiple strands of evidence, which all converge at the same and simplest conclusion. You must decide, gentlemen of the jury, whether you are convinced.»

He says he’s certain that this is the psalter listed in Canterbury’s 1321 inventory of valuables and that the monks accepted it as having been Becket’s. Not a shred of evidence has led him to doubt that they were right, he says.

The idea that it belonged to Aelfric and Alphege is supposition but «overwhelmingly likely» he adds, and it is even more likely that Becket thought it was Alphege’s.

«Fascinating hypothesis» is the verdict of de Hamel’s successor as Parker librarian at Corpus Christi College, Dr Philippa Hoskin.

But Eyal Poleg, who left his coffee and rushed with de Hamel to the Parker library to gaze excitedly at the psalter, advises caution.

«I think the only thing we can say for certain is that in the 14th Century this is seen as the psalter of Thomas Becket in Canterbury. I think that’s where we start and that’s where we stop.»

There’s no evidence that it actually was Becket’s psalter, he says, and he’s not persuaded that it belonged to Aelfric or Alphege. Also he doesn’t think it was necessarily regarded as a relic of St Thomas of Canterbury. (As he remembers the initial after-lunch conversation, he and de Hamel were talking about sacred texts in elaborate bindings – referred to in Latin as textus – and both remarked that they only knew of one that was a psalter, leading to the sudden realisation.)

Another expert with doubts is Prof Alexander Heslop of the University of East Anglia. He believes the psalter’s capital letters were based on designs created by a master scribe, Eadwig Basan, who is not known to have been working in Canterbury until a few years after Alphege’s death.

None of this necessarily means that de Hamel’s theory is incorrect, though if Heslop is right Aelfric and Alphege may have to drop out of the picture.

«When you’re a medievalist, you’re kind of in the dark, and you’re grasping for things, you’re hoping to find something to hold on to,» says Lloyd de Beer, curator of the British Museum’s forthcoming exhibition on Becket, delayed by the pandemic to the spring. «And the thing about Christopher’s work, because he writes so beautifully, and you read such a kind of compelling story, is that he really brings you very close to this history.»

De Beer hopes more efforts will now be made to accurately date the manuscript.

«There’s just still some work to be done, but that’s what’s great about Christopher, he’s throwing out all these big ideas and the best kind of scholars leave those trails.»

During his six years in exile in France, Becket’s negotiations with Henry II, mostly carried out through intermediaries, succeeded in papering over some of the cracks in their relationship, but there had been no kiss of peace before Becket re-crossed the Channel in early December 1170. Some of those close to him warned him not to do it; others pointed out that martyrdom might be a positive outcome.

Becket massively increased the danger on the eve of his departure by suspending or excommunicating three bishops who had taken part in the coronation of Henry’s son, Henry the Young King, who was now serving as co-ruler. It was this that precipitated the events of 29 December.

Christopher de Hamel believes the archbishop may have read the psalter the night before four barons broke into the cathedral to arrest him and – when he refused to go – killed him with sword blows to the head. He even wonders whether Thomas was holding the psalter when he died, though he acknowledges that none of Becket’s contemporary biographers mention this.

Vespers in the cathedral was coming to an end when the attack occurred in the north transept – it would have been out of sight of the worshippers in the nave, but they would have heard everything. One of the fully armed barons stood guard to prevent anyone coming to Becket’s aid.

People began scooping up his blood almost immediately, in the expectation that it would work miracles – and these soon began to be reported. Canterbury then became for 300 years one of Europe’s main centres of pilgrimage, a fact that the British Museum will emphasise with «extraordinary» loans from across the continent.

In time, the east end of the cathedral was rebuilt in pink-tinged stone around a shrine to Becket, also in pink stone with a golden canopy. The psalter, in its jewelled binding, would have been carried in procession to the altar nearby.

But like everything connected with Becket and his cult, the shrine was destroyed on Henry VIII’s orders in 1538. Officials smashed two stained glass windows that must have depicted the life of Becket, says Anne Duggan, but left others intact, probably because they didn’t realise they contained images of the martyred archbishop. Some of the fragments of stone from the shrine were re-used in Canterbury and have been gathered up over the years.

Apart from that, all that remains are the 146 parchment leaves of the psalter, and it will go on display in the British Museum, along with one of the surviving fragments of rose marble.

«The discovery of this book at Corpus Christi college really provides a kind of tangible connection to Becket’s cult in the Middle Ages at Canterbury,» says Lloyd de Beer. «And considering that almost nothing survives, that’s a really exciting thing.»

Photographs of the Parker Library psalter are courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge