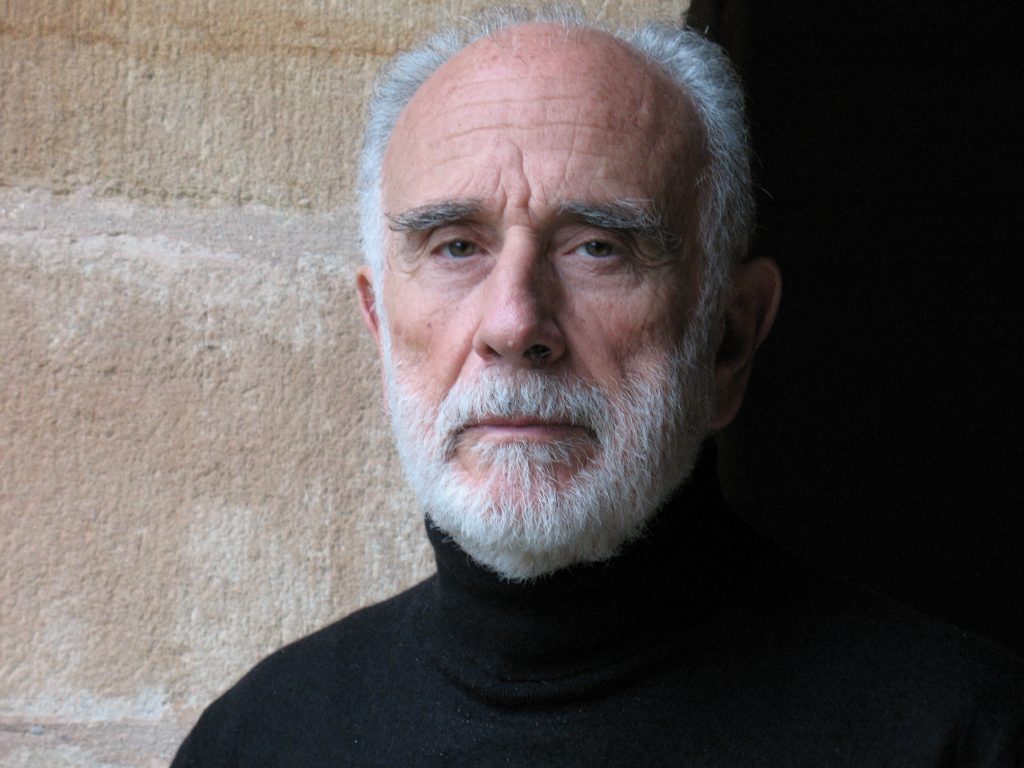

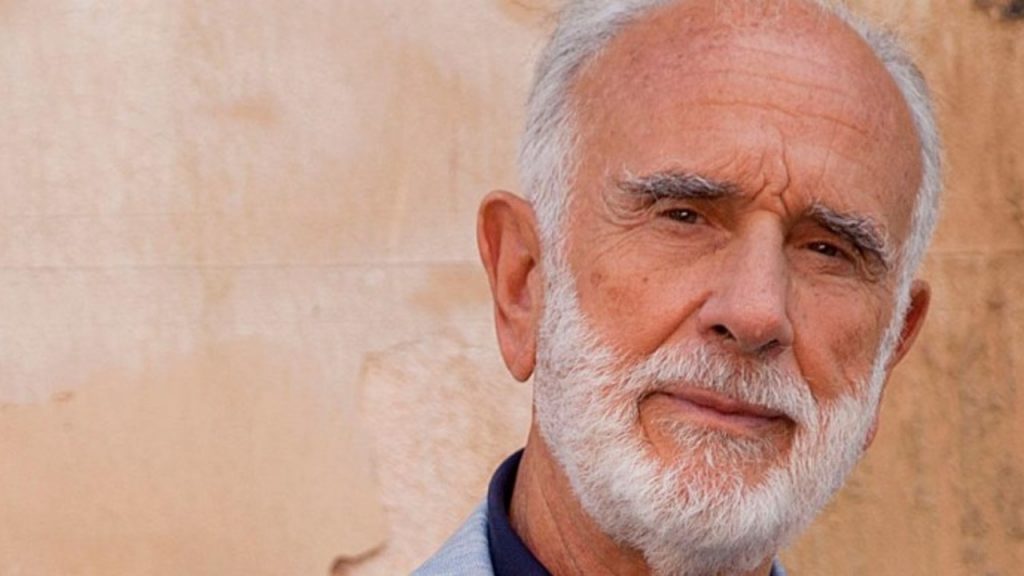

FHB interview with ALFONSO AIJÓN, Founder and President of IBERMÚSICA

Talking to Alfonso Aijón is like reading a novel. The novel of a forced exile full of adventures and hardships. But above all, a passion for music that has always accompanied him and made him the great patron who has celebrated the 55th anniversary of the founding of Ibermúsica, with the humility of the truly great. To mark this anniversary we looked back with him on his devotion to music and the extraordinary adventures of his exile across the world decades ago.

ISABEL AIZPÚN

(Translated by VICKY ASCORVE HARPER)

September 2025

To introduce our interviewee, here are a few facts: in 1983, he received the Order of the British Empire (OBE) from Queen Elizabeth II of England; he is an Honorary Member of the St Petersburg Philharmonic Society; he received the IAMA (International Artists Managers Association) Award for his Contribution to the Profession; he is an Honorary member of the London Symphony Orchestra; he received the Gold Medal from the Granada International Music and Dance Festival; the Medal of Friendship from the Russian Federation; the Grand Cross 1st Class for Science and Art of the Republic of Austria; the Medal of Merit in Fine Arts in Spain; Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany; Alberto Anaut Award; Honorary Member of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Honorary Member of the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Composers Maurice Ohana, Carmelo Bernaola, Mauricio Sotelo and Tomás Marco have dedicated works to him. We can leave it here so as not to overwhelm you any further and ask you how this vocation for music began.

It’s not a vocation, it’s a hobby. I was lucky enough to attend an admirable learning centre, the Ramiro de Maeztu Institute. I remember there were 15 of us in class and we had incredible resources and teachers. Our PE teacher was the head of the Madrid fire brigade, and Carlos Bousoño was our literature teacher. We had microscopes, bookbinding and marketing workshops, two grand pianos… We travelled around the villages of Madrid bringing films and music. I was in charge of the radio and organised weekly concerts when I was fourteen.

Nowadays, you don’t really see young people at classical music concerts

That’s because there’s no music in schools. The contradictory thing in Spain, as with almost everything, is that there have never been so many music schools or so many children learning to play an instrument. That didn’t exist before. Nowadays, there are kids who can play a Mozart sonata at 15, but when they turn 17 their peers, who don’t study music, overwhelm them and they start jumping around on a football pitch. There’s no music for young people because you can’t get into music so late. You have to feel the need for it. Imposing it doesn’t work. I’m not against what’s coming. I wish them happiness, but the truth is that what we have is going to disappear.

Do you consider that you have lived through a kind of golden age of music and culture?

Yes, I am very happy to have lived through the golden age of music, to have known the great names. They all started out in tiny theatres. Now, however, that is not the case. Now, someone with talent comes along and immediately starts conducting a phenomenal orchestra when they have no experience. Just today the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, a very talented Russian Jew, conducted a Bruckner symphony for the first time at a major festival even though he had never conducted a Bruckner symphony in his life.

Times have changed…

Bud Bunny sold 600,000 tickets in 48 hours. And we struggle to fill the Chamber Hall… We are a country of drinking and of football. Eighty thousand people can fit into the Bernabeu stadium, making it almost impossible to get to your house if you live nearby, but if you park your car even slightly badly near the Auditorium, it will be towed away. We haven’t evolved at all.

How could we attract young people?

Start in schools. As it happens in other countries. Politicians are the ones who manage the general budgets and have little training in the humanities, so if young people want pop music, that’s what they get. In European countries music is subsidised by the state. In England and the United States it’s more natural -music is financed with money from enthusiasts and orchestras live off that.

You were Manager of the newly created RTVE Orchestra with Igor Markevitch; Head of Musical Planning at the General Music Commission under the Directorate-General for Fine Arts; and Editor-in-Chief of Spanish Radio and Television. When and how did the idea of founding Ibermúsica come about?

I have always listened to a lot of music. In 1966 I saw an advertisement announcing that the Radio Television orchestra was being formed, and I wrote a letter to Fraga. I was just one person among 40 million of others. I must admit that within 24 hours his secretary called me and invited me to meet him. When I arrived, I walked past several civil governors who were waiting for an audience. We spoke for half an hour as he was very interested in the subject, but when I told him that I thought the future lay in the communist countries he jumped up from his chair. I had said this because I had seen that the spiritual and cultural life there was superior to ours. I had seen that the Bible was available on the black market and that, for example, in Bucharest “La novela picaresca en España” (The Picaresque Novel in Spain) was a sold-out book. The cultural level was incredible.

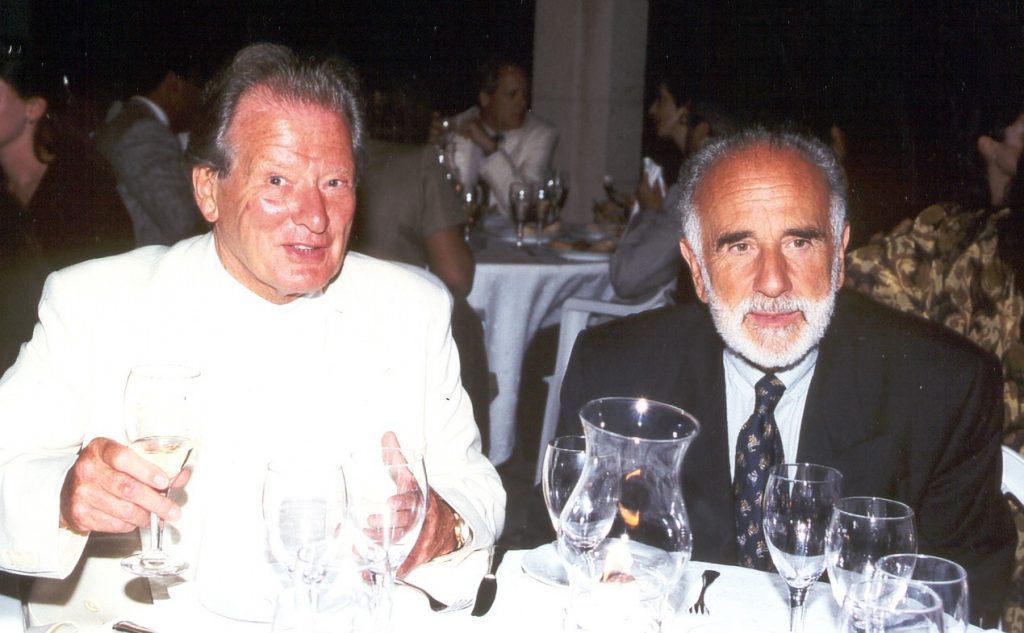

As for Ibermúsica, it was founded in 1970, 55 years ago. When I was very young, I went to all the concerts and listened to young people giving their first concert. When I saw that they had talent, I invited them for a drink and over time I got to know many of them. When I returned from exile, the people I had helped years before were now Zubin Mehta, Barenboim… They said to me: Alfonso, we’re in a good position now and you’re mad about music, so why don’t you set up an agency? And I said, why not? The truth is that it’s a miracle we’ve managed to maintain our standards for so long. I’ve gone bankrupt three times. I’ve even had to mortgage my house to keep Ibermúsica going. I’m happy because I’ve presented more than 800 concerts and 80,000 musicians.

What were the great geniuses you knew like?

I lived through the golden age of the great pianists. I have heard them all. I knew Rubinstein well, as he came to Spain from Poland and gave his first concert in San Sebastián, the first Brahms concert. That’s where he became famous. He was very flirtatious and a womaniser. There is a photo of him dressed as a bullfighter. Barenboim told me one day that when he played, there were many women waiting for him. There is a lot of talent now, but if I had to single out someone among the most recent, I would mention Sokolof and also the Spanish violinist María Dueñas. She is an incredible, wonderful violinist. There is talent, but these days everything moves very quickly.

But there is another side to Alfonso Aijón’s life, full of adventures and incredible episodes that you recount with humour and in accordance with your three rules for living: never get angry about anything; whatever happens is for the best; and walk 8 kilometres a day.

Yes, they are three fundamental rules. If you apply them, everything will go well. I dropped out of law school in my second year, in 1957. If I hadn’t dropped out, my life would have been very different.

My friends were in prison because we were opposed to the regime. Franco’s supporters today did not live through that era, they criticise everything, but some things were not so bad. When I worked at the Uruguayan Embassy in Madrid, the Embassy secretary was a man from Navarra who worked in the office in the mornings and for the secret police in the afternoons. He was there because he had got married at the Uruguayan Embassy during the Republic and the embassy didn’t know he belonged to the secret police. We became friends and he warned me about my friends’ arrests and advised me to leave the country.

I spent ten years outside Spain and got to know a life and a world that no longer exists. I left Spain with 500 pesetas and worked out of necessity, so I’ve done everything: I’ve been a gravedigger in Germany, a farmer in the Alps, a miner in Germany…

About being an undertaker, who offered you that job?

They didn’t offer it to me, I found it myself. It was a different world back then, a time when you could hitchhike without any danger and get a lift every 50 km to wherever you wanted to go. In Germany it was even better because the war had just ended and there were no workers. You’d hitchhike and someone would come along and say, ‘Could you help me pick potatoes?’ And you’d spend a week picking potatoes and so on, working at one thing or another… I made it all the way to Lapland.

And what was the hardest job, gravedigger, miner, potato picker…?

Oh, the worst, without a doubt, was working in a bank. My time in a European bank was the worst because of the tremendous intrigue that existed, because of how employees treated each other in order to get ahead within the bank, especially among middle management. I remember that two signatures were required for large loans. The second person was always waiting to see how the important person signed so they could find some fault with their signature.

I was there because I was fed up with working in a coal mine – but at least there was camaraderie there. I had written to a friend, a schoolmate who was the director of a Spanish bank in New York, and he recommended me to that Spanish bank based in Hamburg. The truth is that in Germany I met some great composers.

Did you find your place in Germany?

I was left-wing, coming out of Franco’s regime, and that was Adenauer’s Germany. Everyone there was very religious. I was working in a metal factory when the village priest discovered that I played the piano and he asked me to play the organ, but on Sundays he would make political propaganda in the church and I was very disappointed. So I left for the socialist countries. I went in red and came out pale pink. It was the Khrushchev era and life was terrible. I was also in Bucharest, at the Uruguayan consulate.

We could say that you have had a rather unusual diplomatic career

My father went bankrupt, and at that time a classmate of mine, who was the son of the Uruguayan ambassador, found me a job as secretary to the ambassador in Madrid. At the embassy, I met a chap who was Consul General in Bucharest. He called me because I spoke languages and I wanted to get to know the communist countries up close. I stayed there for a year and a half. During that time I went to all the Western parties because we had fun messing around with the secret police who followed us everywhere. The consulate had jurisdiction over the entire Black Sea region and I was in Odessa and Kiev, which was wonderful. They are very good at music; all the good pianists are Ukrainian. I was also able to go to Hungary, which was always different. The Hungarian communists, due to their proximity to Vienna, were much milder; life was different there.

The Uruguayan consul general in Bucharest was involved in smuggling disguised as a good deed. It turned out that in communist countries, Jews could leave if they paid $5,000, and this consul was using me. He took my passport, and I couldn’t enter or leave. He used me, and I had to go disguised at night to the home of a Jewish family. They gave me gold, or a Picasso painting, or something valuable, and I took it to the embassy. He took it out in a diplomatic bag and sold it in Vienna through a charity. That money was used to rescue Jews, although other goods such as silk stockings, women’s products, tobacco and Bibles were also bought for the black market. He would come with a full car load and would sell it all to a gangster, but I didn’t like that. I realised that I could be getting involved in those operations.

And after Bucharest, where did your ‘diplomatic life’ continue?

On my way back to Germany, I passed through Vienna, where Uruguayan diplomacy in Europe was centred. I greatly admired the Uruguayan ambassador in Vienna, a Jewish professor, and went to greet him. I met a young man who said to me, ‘Ah, you’re the one who works for free in exchange for food and lodging. Would you like to go to Hong Kong?’ And I thought… why not?

It seems that ‘why not?’ has been a motto in your life.

The thing was, this man had been appointed Consul General of Uruguay in Hong Kong, but he was the gigolo of a tycoon’s wife and possibly wondered why he should be going to Hong Kong when what he wanted to do was be with his lover on the Côte d’Azur. So he said to me, ‘Go, I’ll pay for your trip and I’ll come when I can.’ He showed me his signature and I was able to forge it perfectly. I arrived and had no idea about English. The cleaning lady knew more than I did because she sang Frank Sinatra songs. I had a fantastic room in the best hotel in the world, the Peninsula in Hong Kong. It was an incredible place, with its colonial atmosphere of all the British people at tea time and its incredible view of the bay.

I was in Hong Kong for two years and took the opportunity to visit China during the Mao Tse Tung era. You wouldn’t believe how much it has changed. There was a club in Hong Kong, the Marco Polo, where Chinese cultural events were held every week: piano, theatre, music… They knew I was there and that I wanted to go to China, and one day they invited me to join a Mexican peace group invited by the government. There were 354 of us Mexicans travelling by bus. In communist countries at that time, you couldn’t see what you wanted to see, only what they wanted you to see. In China, however, they stopped us wherever we wanted. We asked people how they lived. And they told us, ‘We used to be miserable, now we’re poor.’ That was in 1963. When you go there now and see the roads, everything. They work at such a pace. They are incredibly ahead of us. They worked around the clock and at night. There were incredible concert halls. They made noise, drank beer, the usual, but now they are an admirable audience.

On the subject of music, Queen Elizabeth II also awarded me the Order of the British Empire, which was wonderful.

I was presented with it at a lunch where the ambassador, during dessert, played a Mozart sonata on the piano in my honour. When the Queen came to visit Spain, I was invited. She was very kind. She greeted me and I gained a lot of confidence in myself because she was smaller than me (ha ha). I was also able to greet King Charles III.

As I was saying, music in the United Kingdom is more authentic because the orchestras don’t have salaries; they live off their work, off their tours. Music is paid for by those who really love it. When they go out to look behind the stage curtain to see how many people are there, it’s because they live off the box office. Only the BBC and Covent Garden have fixed salaries.

For many years, London was the centre of European music because many music centres on the continent were destroyed by the war, and giving a concert in London was a refuge for foreign soloists.

We have brought many British musicians who did not even know Spain, and now they have built their homes and live on the coast. Thirteen British composers have premiered their symphonic works in Spain. I get on very well with English musicians because they are very human, they are people who live from their work. Any famous conductor arrives in London and comes down from the pedestal because there the musicians are the ones who hire the conductors. Nowadays conductors are softer than before, they don’t dare call out the musicians as they did in the past.

You often say that you have always been lucky, even though circumstances have sometimes been tricky.

I am incredibly lucky. I entered Germany from France and needed a visa. I didn’t have one, we arrived at the border and the police wanted to send me back. They put me in a room and suddenly a border police officer arrived, asked why I was there, paid for the visa and I entered. I went two days without eating and saw a truck collecting blood and they gave me food there. I know what it’s like to sleep on benches and go hungry. In Vienna I slept on a bench in front of the best hotel in Vienna, the Imperial, but I never thought of going back. Of course, whenever I go to Vienna, I go to the Imperial, but they’ve taken away my bench…

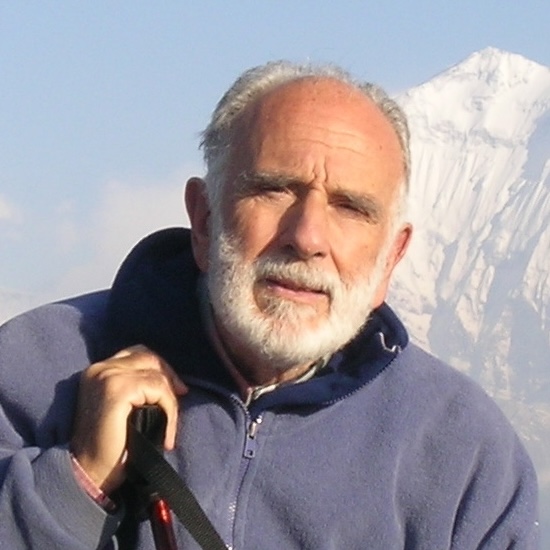

I was able to visit the palaces of a Moroccan caliph whose son was a schoolmate of mine. In the 1940s, they were like the palaces of the Arabian Nights. Also Egypt, Burma, Nepal, Japan. A long time ago, in Pakistan and Afghanistan, when they saw you coming down from the mountains (I am a mountaineer), they would wait for you with a hammock and yoghurt. Before, travelling was a luxury. I have returned to many places and been greatly disappointed. The layout of cities has changed and they are all the same. If I had stayed, I would not have had this life.

DATES OF FIRST PERFORMANCES BY BRITISH ORCHESTRAS WITH IBERMÚSICA AND SUBSEQUENT NUMBER OF CONCERTS

| 1973 | Presentation in Spain | ACADEMY OF ST MARTIN IN THE FIELDS Sir Neville Marriner | 144 |

| 1973 | Presentation in Spain | LONDON MOZART PLAYERS Henry Blech | 4 |

| 1973 | Presentation in Spain | GABRIELLI QUARTET | 4 |

| 1974 | Presentation in Spain | LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf | 242 |

| 1974 | Presentation in Spain | ROYAL PHILHARMONIC OCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf | 80 |

| 1974 | Presentation in Spain | THE NASH ENSEMBLE Sir Simon Rattle | 6 |

| 1977 | Presentation in Spain | ST JOHN SMITH SQUARE ORCHESTRA Lubbock | 10 |

| 1980 | Presentation in Spain | BBC SYMPHONY Gennady Rozhdestvensky | 4 |

| 1981 | Presentation in Spain | LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Jesús L.Cobos | 93 |

| 1982 | Presentation in Spain | THE SCOTTISCH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA James Conlon | 3 |

| 1982 | THE ENGLISH CONCERT | 5 | |

| 1984 | Presentation in Spain | LIVERPOOL SYMPHONY Marek Janowski | 3 |

| 1984 | Presentation in Spain | DELLER CONSORT | 1 |

| 1984 | Presentation in Spain | PRO CANTIONE ANTIQUA | 4 |

| 1985 | Presentation in Spain | CHAMBER ORCHESTRA OF EUROPE Paavo Berglund | 37 |

| 1986 | PHILHARMONIA Vladimir Ashkenazy | 114 | |

| 1986 | Presentation in Spain | BOURNEMOUTH SYMPHONY Rudolf Barshai | 9 |

| 1986 | Presentation in Spain | LONDON VIRTUOSI | 10 |

| 1986 | Presentation in Spain | ORQUESTA NACIONAL DE ESCOCIA Neeme Jarvi | 6 |

| 1987 | Presentation in Spain | CITY OF LONDON SINFONIA Richard Hickox | 9 |

| 1987 | Presentation in Spain | LONDON BACH ORCHESTRA Nikolas Kraemer | 5 |

| 1988 | Presentation in Spain | THE ANCIENT MUSIC ORCHESTRA Christopher Hogwood | 5 |

| 1988 | Presentation in Spain | HALLE OCHESTRA Skrowazewski | 4 |

| 1988 | Presentation in Spain | NORTHERN SINFONIA J.Bernard Pommier | 8 |

| 1990 | Presentation in Spain | CITY OF BIRMINGHAM ORCHESTRA Sir Simon Rattle | 13 |

| 1994 | Presentation in Spain | BBC PHILHARMONIC J.P.Tortelier | 2 |

| 1995 | Presentation in Spain | KING´S CONSORT Robert King | 10 |

| 2010 | MONTEVERDI CHOIR Sir John E.Gardiner | 1 | |

| 2019 | THE AGE OF ENTLIGHTEMENT | 1 | |

TOTAL PERFORMANCES | 837 |

BRITISH COMPOSERS AND THEIR PREMIER IN SPAIN OF HIS SYNPHONIC WORKS

| G.BENJAMIN |

| B.BRITTEN |

| P.M.DAVIES |

| E.ELGAR |

| G.HOLST |

| H.KENDALL |

| O.KNUSSEN |

| J.MC.CABE |

| J.MAC MILLAN |

| C. MATTHEWS |

| N.MAW |

| M.TIPPETT |

| V.WILLIAMS |